Topic Five

Mexican Farm Worker Unionization, 1930-1960

During the Great Depression, ethnic Mexicans viewed labor organizing campaigns as part of the promise of equality and civil rights. During this time, Santa Clara County saw some of the most significant agricultural strikes in the U.S., many involving Mexican workers. Before WWII, most Mexicans worked on farms in the fruit and nut orchards or tomato and pea field/row crops. The Depression of the 1930s saw a deterioration in working conditions and a dramatic decrease in pay for orchard and field workers, who were paid by piece work rather than hourly wages. Historian Glenna Matthews claims that weekly pay dropped from $16.33 in 1929 to $8.04 in 1933. Growers stopped working cooperatively in the fruit exchange and began selling their crops individually, competing with each other and lowering wages even further. During the New Deal, between 1933 to 1937, the federal government supported farmers by buying their crops, thus propping up prices.

In 1931 the new Cannery and Agricultural Workers Industrial Union (CAWIU) set up its state headquarters in San José at 81 Post Street, charging monthly dues of twenty-five cents for the employed and five cents for the unemployed. Dorothy Ray Healey, Elizabeth Nicholas, Pat Chambers, and Caroline Decker were among the CAWIU organizers working in the county. The CAWIU undertook thirty-seven agricultural strikes in California. Historian Glenna Matthews contends that Santa Clara County, as in the rest of the nation, saw more strikes and violence in 1933 than ever before, with three agricultural strikes and one brutal non-agricultural-related lynching.

In April of 1933, 2,000-3,000 pea pickers, composed of Mexicans and Dust Bowl migrants working near the Milpitas/De Coto County line, struck for higher wages and lost. In June 1,000 cherry pickers, mostly Spanish workers from the Mountain View area, struck for higher wages. That same year, the cherry picker strike was considered the most violent of the three strikes in Santa Clara County. Workers were successful and won a 50-percent raise, from twenty cents to thirty cents an hour. According to the La Follette Civil Liberties Committee Report (1936-1941), the cherry pickers were successful because the Spanish workers were homeowners and had invested in their communities, unlike the migrant Mexican and Dust Bowl pea pickers.

In August 1933 pear pickers staged a strike, CAWIU’s most successful strike in the County, largely due to organizer Caroline Decker, who gained the support of the Palo Alto Democratic Club. In turn the Democratic Club, state and federal government officials, and the California Bureau of Labor Statistics backed the union’s right to picket, opposing the growers who had obtained an injunction against picketing workers.

The Bracero Program made it difficult to organize farmworkers throughout the Southwest, as well as Santa Clara County, because braceros were used as strikebreakers until the program ended in 1964. Ernesto Galarza organized agricultural strikes (though not in Santa Clara County) using the National Farm Labor Union during the 1940s and 1950s.

In 1937, workers in thirteen dried fruit companies decided to unionize. They organized the Field Practice Group and initially contracted with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), considered a “company union” less concerned with non-white members, who represented 98% of the dried fruit workers of Santa Clara County. Unlike cannery workers, in 1941 dried fruit workers left the AFL and voted for representation from the more left-wing CIO, which promoted for the largely Mexican workforce higher wages, retirement benefits, and a hiring hall instead of a shape up.

Title: Mexican grandmother of migrant family picking tomatoes in commercial field. Santa Clara County, California

Creator(s): Lange, Dorothea, photographer

Date Created/Published: 1938 Nov.

Rights Advisory: No known restrictions.

Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Collections: Farm Security Administration/Office of War Info. Black-and-White Negatives

Part of: Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection

Permalink: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2017770799/

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

Mexican Cannery Worker Unionization, 1917-1960

The first Santa Clara County cannery strikes took place in 1917 with the AFL’s Toilers of the World. According to historian Glenna Matthews, the Toilers signed a two-year contract that only benefitted male workers. Not until the 1930s did women cannery workers find a union voice.

Initially, cannery and field/orchard work were seen as components of the larger agriculture industry and excluded from government-sponsored protections afforded to industrial workers under the 1935 National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) or The Wagner Act. By the 1930s, as more mechanization was introduced, cannery and packinghouse labor gained protections offered to industrial workers. According to historian Glenna Matthews, canners strengthened their efforts to fight unionization during the 1930s with the formation of the Canners’ League. The 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act stipulated that competing companies within an industry should cooperate, which the fractured growers resisted.

During the Great Depression, Santa Clara County canners faced a harsh economic future. Profit margins were dropping, executives took pay cuts, and small canners went out of business. According to historian Glenna Matthews, during that decade CalPak reduced production by one third. Processors tried to reduce expenses by lowering workers’ pay.

With the first dramatic decrease in wages, in 1931 cannery workers fought back with their first strike under the Cannery Agricultural Workers Industrial Union (CAWIU). Dorothy Ray Healey and Elizabeth Nicholas were among the organizers, with Dorothy taking the lead with cannery workers. A few months prior to this strike, Italian and Spanish cannery workers formed the American Labor Union and revealed the harsh conditions cannery workers faced. In 1931 the CAWIU set up picket lines at several canneries. Workers were arrested, and in July 2,000 workers held a rally in St. James Park, demanding that police release jailed picketers and triggering the worst riot in San José history. In response Richmond-Chase cannery set up machine guns at its gate, and CalPak threatened to ship its fruit to distant canneries. The strike was lost, and the CAWIU shifted its focus to unionizing agricultural workers.

The 1931 cannery strike developed future cannery union leaders who joined the struggle for worker representation led by the American Federation of Labor (AFL). The AFL was seen as a “company union,” not taking the grievances of cannery workers seriously, particularly those of Mexican women. At the end of the 1930s, the AFL battled the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) for cannery worker representation and won the struggle. By the end of the 1930s, all San José canneries were unionized and remained so until the last one, Del Monte Plant #3, closed in the 1990s, with union representation shifting back and forth. In 1945 the AFL relinquished its control of Santa Clara County cannery workers to the Teamsters, who neglected the rights of non-white cannery workers. Union representation returned to the AFL, which merged with the more left-wing CIO in 1955. By the 1950s many Mexican cannery workers had gained unemployment insurance, a livable wage, and benefits for the first time. In 1967 under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, jobs could no longer be classified as “male” or “female,” so women could enter the more lucrative warehouse jobs previously controlled by men. Through the unions, Mexicans were able to earn the salaries needed to settle permanently in the colonias and become homeowners.

Title: Women Strikers at CalPak Plant #9 [California Packing Corporation Pickle Plant. became Del Monte, located at Jackson and N. Seventh Streets, San José]

Date: c. 1931

No: ECS1770

Collection: Edith C. Smith Collection

Source: Sourisseau Academy

- Remote video URL

Ernesto Galarza’s Background

Dr. Ernesto Galarza was born in 1905 in the village of Jalcocotán near Tepic, Nayarit, México. In 1911, he came to the U.S. with his mother and uncles to escape the Mexican Revolution. After losing his mother and uncle to influenza, Galarza lived in the Sacramento barrio working as a farm laborer. His surviving uncle made it possible for him to continue his education. At age eight, he knew more English than the adults in the labor camp and became a spokesman for them, highlighting their poor living conditions. Galarza understood that education was essential and to finance his schooling, took jobs as a messenger, clerk, court interpreter, and field and cannery worker. He would later chronicle his childhood in the autobiographical novel Barrio Boy, published in 1971.

Encouraged by his teachers, Galarza entered Occidental College in Los Angeles on a scholarship in 1923. After completing his B.A., he obtained an M.A. in history from Stanford University and then in 1944 a Ph.D. in economics from Columbia University. While at Columbia, Galarza worked for the Pan-American Union (1936-1947), serving as chief of the Division of Labor and Social Information. Although he left this job to become a labor organizer, Galarza was viewed as an intellectual and scholar whose weapons were words. Recognized as a poet, author, and educator in his later life, he taught at every level from elementary school to university and was a lifelong advocate for bilingual education.

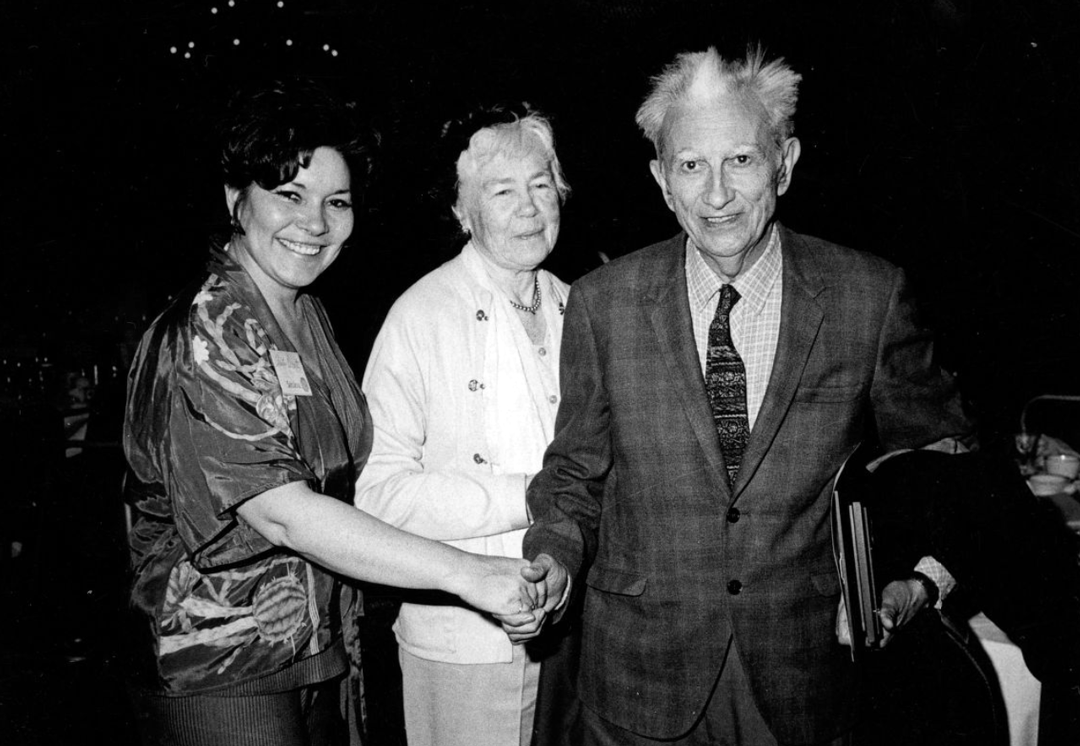

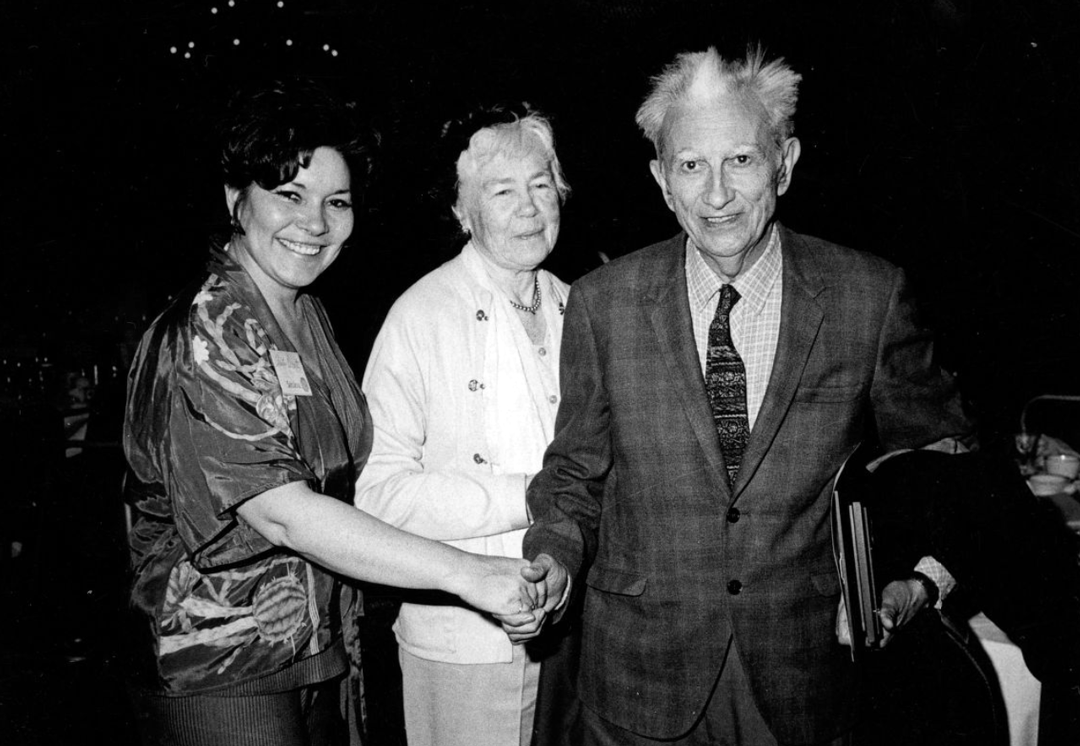

Title: Ernesto Galarza and wife Ann

Date: 1989

Location: Series II, Box 6, Folder 3

Collection: Ted Shl Archives

Source: Special Collections, SJSU Library

Ernesto Galarza NFLU and The Bracero Program

Through his research, Galarza came to understand that one of the major obstacles to unionizing Mexican farmworkers was the 1942 Mexican Farm Labor Program Agreement, better known as the Bracero Program. He left the Pan-American Union outraged by their acceptance of U.S. corporations’ exploitation of Mexican labor. In 1947 he became the director of research and education in California for the AFL-CIO’s National Farm Labor Union (NFLU) previously known as the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, which included black and white tenant farmers and agricultural laborers who organized for better wages, working conditions, and favorable legislation for small-scale farmworkers. In 1948 Galarza became vice president of the NFLU and was deeply involved in over a dozen unsuccessful strikes between 1947-1954, including tomato pickers in Tracy, cantaloupe pickers in Imperial County, and at the DiGiorgio Fruit Corporation. Outside of California, he organized sugar cane workers and strawberry pickers in Louisiana.

In 1952 NFLU became the National Agricultural Workers Union (NAWU), and Galarza became its secretary from 1954-1963. Strikes were impossible to win because braceros would replace strikers as strikebreakers, and Galarza left labor organizing determined to use his writing skills as a weapon to help end the Bracero Program.

Galarza had visited bracero camps and saw firsthand how employers used braceros to break strikes and avoid union organizing. Bracero labor also depressed wages for American workers. Galarza exposed abuses within the Bracero Program in his best-known work, Merchants of Labor (1964), which helped to end the program and laid the groundwork for César Chávez to begin the United Farm Workers of America (UFWA) in 1965.

Galarza became a labor organizer because he believed that to achieve civil rights, Mexican Americans and labor unions needed to work together to address workplace and community problems. Between 1963-1964, Galarza served as advisor to the U.S. House Committee on Education and Labor. In 1979, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature for his writing on braceros.

Title: NFLU Leadership c. 1940s

Collection and No: Ernesto Galarza Papers

Source:: Special Collections, Greene Library, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

Legal Challenges to Segregation

School segregation was a major issue for Mexicans in California and Texas. Groups of parents filed numerous lawsuits to push local governments to integrate local schools. These struggles united parent groups and LULAC (The League of United Latin American Citizens), and together they fought landmark cases such as Del Rio ISD v. Salvatierra in Texas (1930) and Roberto Alvarez v. the Board of Trustees of the Lemon Grove School District, often referred to as “The Lemon Grove Incident,” in San Diego, California (1931).

LULAC, the first national Mexican American Civil Rights organization, was established in 1929 by American citizens of Mexican descent in Corpus Christi, Texas. Until WWII, LULAC undertook several school desegregation court cases in Texas and California using the argument that Mexicans were white. Accordingly, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) gave American citizenship to Mexicans living in the U.S. territory at the end of the Mexican American War while the U.S.Constitution had stipulated that only white males were eligible for U.S. citizenship. This legal argument was not successful.

After WWII, LULAC worked with the Mexican consulate and the NAACP to strategize for Mendez v. Westminster (1947). This California Supreme Court case repealed all segregation in California schools, arguing that the 14th Amendment provided for “equal protection” under the law, and influenced the landmark 1954 U.S. Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education Topeka, Kansas. In 1954, lawyers from the American G.I. Forum and LULAC argued in the U.S. Supreme Court case of Hernandez v. Texas that the Mexican American defendant was denied “equal protection” under the 14th Amendment. The court granted that Mexican Americans were “a class apart,” not easily fitting into a legal structure that only recognized blacks and whites. Direct action on segregation, including strikes, walkouts, and boycotts, would come much later.

Title: Mayfair School Class Portrait with Christmas Tree, c. 1940

Date: 1935-1950

Collection: History San José Online Catalog

Owning Institution: History San José Research Library

Source: Calisphere

Permalink: https://calisphere.org/item/ac5699114d7befb729677d8c6cae3988/

The League of United Latin-American Citizens: A Texas-Mexican Civic Organization

Jan. 5, 1931: Lemon Grove Incident - Zinn Education Project

Background - Mendez v. Westminster Re-Enactment | United States Courts

April 14, 1947: Mendez v. Westminster Court Ruling - Zinn Education Project

Mendez v. Westminster School District | National Archives

American Latino Theme Study: Education (U.S. National Park Service)

The American G.I. Forum

WWII brought a new awareness of racial issues as the military began to integrate under Executive Orders in 1941 and 1948, though full integration would not come until 1960 for some branches. Anglo American GIs shared bunkrooms, meals, and social time with their Mexican counterparts and understood that they had to rely on one another in combat. Although Mexican Americans did not face the same level of segregation in the military as African Americans and lighter skinned Mexicans were sometimes classified as white, they understood that racial prejudice still remained.

As Mexican veterans returned home, they continued the fight for the “Double V for Victory”–victory against racism abroad and at home. When Mexican American veterans were banned from participating in local veterans’ groups and denied services at veterans’ hospitals or military cemeteries, in 1948 they formed the American G.I. Forum, which welcomed all veterans of color.

The GI Forum was founded in Texas by Dr. Hector P. García to fight discrimination against Mexican Americans in employment, education, and access to veterans’ benefits. The organization gained national attention when it took up the Felix Longoria case in 1949. Longoria, an ethnic Mexican veteran from Texas killed in the Philippines, was refused burial in his hometown, Three Rivers, Texas. The GI Forum appealed to then-Senator Lyndon Baines Johnson, who had seen discrimination first hand in Texas after teaching in a segregated school for Mexican Americans. In the Longoria case, Johnson intervened, arranging for him to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors at no cost to his family.

The San José chapter of the Forum was formed in 1949, focusing on youth issues and offering scholarships. In 1960, the Forum collaborated with other groups, such as the Community Service Organization (CSO), on voter registration campaigns and advocating for ethnic, minority and disenfranchised communities.

Title: Conrado Barrientos US Air Force, WWII

Collection: Before Silicon Valley Project Archives, Barrientos Collection

Owning Institution: Special Collections, San Jose State University

Fr “Mac” McDonnell and Guadalupe Church

Father Donald McDonnell was a member of a group of Catholic priests, the “Spanish Mission Band,” who worked with Mexican farmworker communities. Initially Fr. McDonald served at St. Joseph Church in the Mountain View colonia (1947-1951), encouraging the formation of Club Estrella as well as a community credit union. In 1952 he moved to Eastside San José and introduced parishioners to non-violent community organizing strategies, urging them to address racial discrimination through action. Known as “Father Mac,” he was familiar with Ernesto Galarza’s writings and agricultural union organizing, and instructed parishioners on labor law, focusing on abuses of the Bracero Program.

The Eastside had no Catholic church to serve the growing Mexican population, and Father Mac helped parishioners to establish the Guadalupe Chapel. In 1953, the Catholic Church purchased an old church building, disassembled it, and moved it to the Mayfair district. It was reconstructed by parish volunteers, including siblings César and Richard Chávez and their sister Rita Chávez Medina. The building housed the growing Our Lady of Guadalupe congregation until it was replaced in 1968. The chapel also served as the first headquarters of the San José chapter of the Community Service Organization (CSO), which trained community organizers and conducted campaigns for social justice and labor rights. Because of this history, Fr. McDonnell Hall, originally the Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel, is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places (2016) and became a National Historic Landmark in 2017.

Filename: Guadalupe Mission, c. late 1950s. Cropped-Guadalupe Church Photo Album-Chavez Photos-7595.tif

Collection: Before Silicon Valley Project Archives, Guadalupe Church Photo Album

Owning Institution: Special Collections, San Jose State University (after Sept 30, 2023)

The CSO and Fred Ross

According to historian Gabriel Thompson, Fred Ross, Sr., was born to an affluent and politically conservative family from Los Angeles. He attended the University of Southern California, where he was exposed to politically liberal ideas. Ross wanted to be a teacher, but after his graduation in 1936, due to the Depression, he took a three-year term as a relief worker. He then became manager of the federally-funded Farm Security Administration (FSA) Arvin Migratory Camp for Dust Bowl migrants located near Bakersfield. He replaced the previous corrupt manager and tried to regain the workers’ confidence by forming a workers’ council and supporting a cotton strike. During his time at Arvin Camp, he met folk singer Woody Guthrie and listened to his songs of political protest.

During WWII Ross worked for the War Relocation Authority in Cleveland, finding jobs and housing for Japanese Americans not placed in internment camps. After WWII, he returned to Los Angeles to work for the American Council on Race Relations, organizing “multi-racial unity leagues.” He led voter registration drives to force out racist local politicians and desegregate schools. His work contributed to the successful 1948 California State Supreme Court decision in Mendez v. Westminster. Ross also worked for Saul Alinsky’s Chicago-based Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF). In 1947 he was hired to promote Latino political power in Los Angeles.

That same year, in Boyle Heights, a Los Angeles neighborhood with a large Mexican population, Ross formed the first chapter of the Community Service Organization (CSO), which was established to protect the civil rights of Mexican Americans and foster political and civic engagement. Fred Ross approached social worker Edward Roybal and Antonio Rios, a union organizer with the United Steelworkers of America, with the idea of forming a community-based organization. In the IAF model, an outside organizer works with local leaders to create a democratic organization where people can identify their concerns and address them through direct action. Edward Roybal became the first president and main spokesman of the CSO’s LA Chapter.

Building on the earlier work of mutualistas, church groups, and community associations, the CSO stressed voter registration and held citizenship classes to promote political involvement. They also addressed ongoing problems such as poor community services and discrimination in housing, education, and employment. After WWII, Mexican American and African American civil rights groups occasionally worked together, though they sometimes differed in their aims and goals. For example, education was an important issue for both groups, but bilingual education was extremely important to Mexican Americans, while busing was a higher priority for African Americans. Fair housing and employment legislation were key issues for both, but Mexicans prioritized pensions for resident non-citizens, who were often not eligible for social services.

CSO members learned the importance of becoming activists in their own communities. By 1963, the CSO had 34 chapters across the Southwest, registering 500,000 new voters and helping over 50,000 Mexican immigrants obtain citizenship in California. In 1949, utilizing the community organizing skills of Fred Ross, Sr., and CSO volunteers, Edward Roybal was elected to the Los Angeles City Council. The first Mexican to win a seat since 1881, Roybal was later elected to Congress, serving from 1963 to 1993.

Title: Fred Ross, 1950s

Collections: Fred Ross Papers

Source: Special Collections, Greene Library, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, CA

The Formation of the San José Chapter of the CSO

In 1951 San José State College sociology professor and American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) member Claude Settles brought Fred Ross, Sr., to campus to give a lecture. Herman Gallegos, a student, and Leonard Ramirez and public health nurse Alicia Hernández, two community members, attended that lecture and encouraged Ross to organize a new CSO chapter in the barrio known as “Sal Sí Puedes“ (meaning “Get Out if You Can,” a name that can be traced back to a Mexican land grant) in the Mayfair district of East San José.

Assigned to a project in Kansas City, Ross reached out to his contacts in Santa Clara to provide local assistance and support. One of these was Quaker philanthropist and AFSC member Josephine Duveneck of Los Altos Hills. Duveneck initially provided housing for Fred Ross, Sr., a place to hold meetings, and financial support. In 1952 Ross was assigned by Saul Alinsky to work in San José, and shortly upon arrival, he sought out Father McDonnell to help identify potential organizers, such as Guadalupe-parish member César Chávez.

Ross’s community organizing techniques were based on door-to-door canvassing and house meetings. Volunteers such as Rita Chávez Medina (César’s sister), Herman Gallegos, and César Chávez went door-to-door in the Eastside’s crowded neighborhoods, over unpaved streets, registering voters and talking to residents about how to form a CSO Chapter. The community was ready, and the formational meeting took place at Mayfair Elementary School in 1952. Meetings were later moved to the Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel, where the CSO established its first offices, local campaigns were planned and organized, and volunteers were trained.

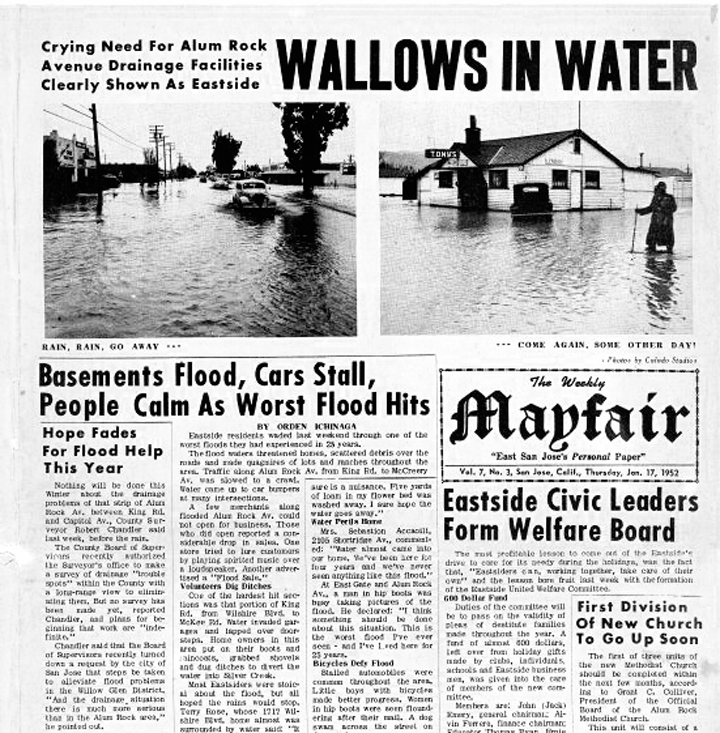

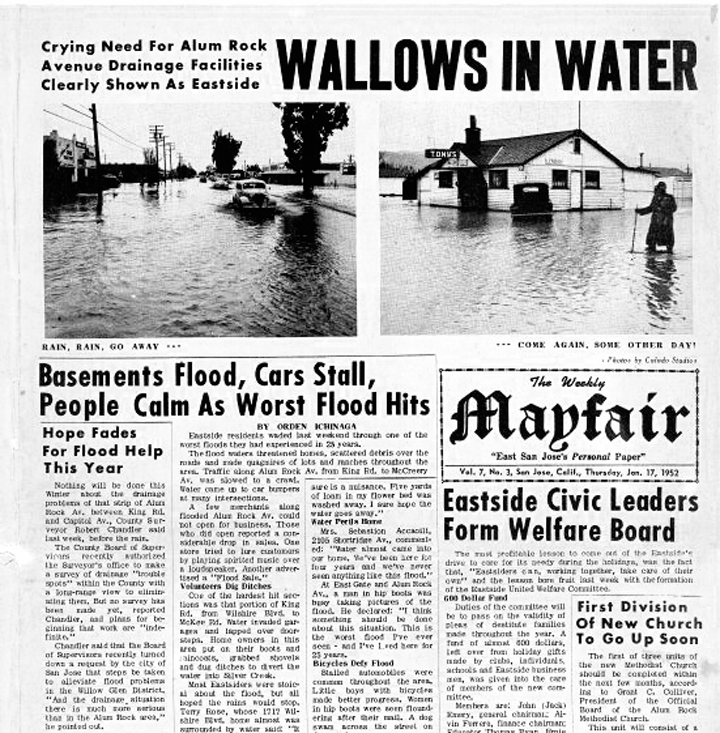

Filename: FAIR USE_HSJ The Weekly Mayfair_Flooding East Side_Jan 17 1952_CROP_2006791.jpg

Objectid: 2006-79-1

Caption: Mayfair_19520117_p01

Owning Institution: History San Jose

Permalink: https://historysanjose.pastperfectonline.com/media/947D46E1-8C99-4AA2-B387-450801468900

The Founding Members of the CSO San José Chapter, Excluding Cesar Chavez

The following are some of the founding members of the CSO San José Chapter:

Herman Gallegos became the first president of the San José Chapter as well as president of the national CSO in 1960. Gallegos grew up in a poor coal-mining family who lived in a mud hut built by his father near the mines in Ludlow, Colorado, where he observed the infamous “Ludlow Massacre” of striking workers. After the massacre, the family moved to San Francisco. Gallegos first attended San Francisco State University, where two of his professors, Dr. John Beecher and Dr. Herbert Bisno, refused to sign a loyalty oath required under the Levering Act affirming that the signer was an American and not a Communist or risk being fired. When a state police officer came into the classroom and handed Dr. Beecher a letter requiring him to leave, Gallegos and two Jewish students walked out of class and went to the administration office demanding the professor be reinstated. Because the protesting students did not have a permit, the police broke up the protest, and Gallegos decided to transfer to the Social Work Program at San José State College. When he joined the CSO, he was attending college, living on the Eastside, and working as a gas station attendant. At that time he and Hernández were the only two members of the organization with a college education. In 1960 Gallegos became national CSO president, with César Chávez serving as executive director.

Alicia Hernández, a public health nurse who worked with families on the Eastside, became a founding member after attending Fred Ross’ first talk at San José State College (with Herman Gallegos, Juan Marcoida, and Leonard Ramierez). She became the first temporary chair or interim president of the CSO San José chapter. A friend of Chávez’ wife Helen, Hernández arranged the first meeting between Ross and César Chávez, who was 25 years old. Hernández and Chávez walked door to door in the Eastside registering voters.

Juan Marcoida, another student who heard Ross’s initial talk at San José State, was an engineer who worked by day and went to college at night. He became a founding member of the CSO San José Chapter while working at the General Electric Plant, where he’d been employed since its opening in 1947. A resident of Sal Sí Puedes in the Eastside, Marcoida served two terms as president of the CSO San José Chapter. He also hosted a radio program called CSO INFORME that aired for ten years on KLOK and KSJO radio stations, highlighting jobs, legal issues, police brutality, domestic abuse, immigration, deportation, scams, and voter registration assistance. He was named “1956 Man of the Year” in El Excentrico magazine.

Rita Chávez Medina, the eldest of the Chávez siblings, had quit school at age 12 to help support the family after they lost their farm. She continued to work in the fields, transitioning into cannery work when she married and her family moved to San José. There she became active in local efforts to obtain a Catholic church to serve the Mexican community in the Eastside, enlisting the help of her brothers César and Richard, a union carpenter. She had already demonstrated her organizing skills in the church campaign when César asked her to work on the CSO voter registration drive, and he increasingly delegated local organizing tasks to her. Rita rose to become CSO San José Chapter President.

Leonard Ramirez, who also heard Ross’ speech, and his wife Erma became founding members of the CSO San José Chapter, fighting for paved streets and street lighting as well as promoting voter registration. Ramirez led the CSO drive to abolish citizenship requirements to receive Social Security benefits for old age. The law was revised in 1960 taking out Social Securities citizenship requirement. Ramirez was born in Watts, California, in 1926. After high school, he joined the army during WWII. Through the help of the GI Bill, he graduated from San José State College in 1953, one of only five Mexican students attending the university.

Filename: FAIR USE_HSJ The Weekly Mayfair_Flooding East Side_Jan 17 1952_CROP_2006791.jpg

Objectid: 2006-79-1

Caption: Mayfair_19520117_p01

Owning Institution: History San Jose

Permalink: https://historysanjose.pastperfectonline.com/media/947D46E1-8C99-4AA2-B387-450801468900

The Background, Recruitment and Rise of César Chávez to the CSO

César Chávez was born in 1927, the second of six children in an extended family of devout Catholics, and grew up on his grandparents’ family farm near Yuma, Arizona. In 1939, during the Depression, the farm was auctioned and sold to cover back taxes. César’s father had been diagnosed with a lung disease requiring a move to a cooler climate, and the family joined the growing number of American migrant workers in California. Unlike sister Rita, who quit school at 12 years of age to work in the fields full time, Césario (César) carried family expectations as the eldest boy and was allowed to attend school while working in the fields weekends and holidays. Eventually, he and his family worked across California from Brawley to Oxnard, Atascadero, Gonzales, King City, Salinas, McFarland, Delano, Wasco, Selma, Kingsburg, and Mendota. The essential injustice and underlying racism the family experienced during those years made a strong impression on César. Despite the numerous interruptions to his education, he graduated from the eighth grade in June 1942 and became a full-time farm laborer until he joined the Navy in 1945.

A Navy veteran by 1947, Chávez returned to working with the family as an agricultural laborer. He joined the National Farm Labor Union (NFLU), picking cotton in Corcoran, near Delano. Cesar and his brother Richard both worked briefly in the lumber yards of Crescent City. However, the distance was too far from the rest of the family in San José, so by the 1950s, their sister Rita encouraged César and Richard to relocate their families to San José. Richard became a successful union carpenter, and César continued working in the fields and local lumber yards when, at 25 years of age, he met Fred Ross, Sr., in 1952.

When Ross had begun to look for local organizers for the CSO, Alicia Hernández offered to introduce him to her friend Helen Chávez and her husband César, who had become active in social justice work through his association with Father McDonnell, pastor of the Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel. Through Fr. McDonnell, Chávez had learned the principles of nonviolent resistance and been introduced to Catholic teachings that emphasized social justice and challenged economic and social inequalities. With Father Mac, Chávez had visited labor camps and farmworkers living beyond the Eastside.

Fred Ross encouraged Chávez to become a full-time paid organizer for the Community Services Organization (CSO), and he soon began setting up chapters in the Bay Area and other towns across the state. Named executive director of the national CSO in 1959, Chávez moved to Los Angeles to work in the organization's main office. Though the CSO had become a successful advocate for communities of color, Chávez had not given up the idea of working with farmworkers and felt that the CSO was more focused on the problems of urban communities. In 1962 he left the CSO and moved to Delano, California, with his wife, their eight children, brother Richard Chávez, and Dolores Huerta, another CSO colleague from Stockton, in order to establish a union for farm laborers, the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA)

Filename: FAIR USE_HSJ The Weekly Mayfair_Flooding East Side_Jan 17 1952_CROP_2006791.jpg

Objectid: 2006-79-1

Caption: Mayfair_19520117_p01

Owning Institution: History San Jose

Permalink: https://historysanjose.pastperfectonline.com/media/947D46E1-8C99-4AA2-B387-450801468900

CSO San José Chapter Organizing Tactics

In San José, CSO organizers held house meetings where they identified community concerns, which became the focus of their campaigns, and recruited potential members and volunteers. Formal meetings were then held at the Mayfair School to create an official organization. The main issues of concern to Eastside residents included improving essential services, paving streets, installing streetlights, dealing with police brutality, and addressing economic inequality. Due to the anti-communist fervor of the early 1950s, it was important to involve religious leaders like Fr. McDonnell to assure the authorities that CSO members were not Communists or political agitators, so the opportunity to hold regular meetings at the Chapel was welcomed.

Articles in El Excentrico introduced more people to the organization and emphasized its roots in the local community. Juan Marcoida, CSO member and chapter president, hosted a radio program, CSO INFORME, for ten years on KLOK and KSJO radio stations, with businesses donating to cover airtime costs. CSO services were provided free of charge, and, with so many people in need of help, fundraising was continuous–donated Christmas trees and tamales were sold, musicians played for free at dances, and members held raffles and ran a secondhand store.

Prior to World War II, only a small percentage of Mexican immigrants had filed naturalization papers since citizenship did not appear to improve their working or living conditions. CSO members learned that some problems required legislative remedies to develop better public policy, which made citizenship, and thus citizenship classes, more important. The CSO became part of a civil-rights coalition, including the NAACP, the Urban League, the Jewish Community Relations Committee, the Japanese American Citizens League, and other organizations that met regularly to frame the strategy for public policy involvement in California. By increasing their political power through citizenship classes and voter registration, these groups fought discrimination in education, housing, and employment on local and state levels. In the 1950s, the CSO San José Chapter lobbied to end citizenship requirements for Social Security benefits and promoted voter registration drives with the assistance of the G.I. Forum and worked with the NAACP to challenge discrimination of Mexicans against African Americans.

Filename: FAIR USE_HSJ The Weekly Mayfair_Flooding East Side_Jan 17 1952_CROP_2006791.jpg

Objectid: 2006-79-1

Caption: Mayfair_19520117_p01

Owning Institution: History San Jose

Permalink: https://historysanjose.pastperfectonline.com/media/947D46E1-8C99-4AA2-B387-450801468900

Life After the CSO: Some of the Founding Leaders of the San José Chapter

Alicia Hernandez, who did not like being in the spotlight that can accompany a leadership role, moved to San Francisco to continue nursing.

Leonard Ramierez became a probation officer and helped to open the James Ranch Juvenile facility in Morgan Hill (William F. James Boys Ranch). He became chair of the United Way of Santa Clara County, a founder of the Hispanic Development Corporation, and a member of the GI Forum.

After leaving the CSO in the early 1960s, Fred Ross helped organize residents of Guadalupe, Arizona, primarily Mexican Americans and Yaqui Indians, to gain basic services such as paved roads and stop signs. He then taught organizing skills to students at Syracuse University working on a campaign, supported by federal “War on Poverty'' funds, to organize African American residents living in dilapidated public housing. The idea of paying organizers with government funds to stir up people to challenge government policies proved controversial, and the funding was eventually halted. Returning to California in 1966, Ross became the organizing director of the United Farm Workers Association. He assisted the UFW in a campaign over who would represent workers at DiGiorgio, a major grower in the San Joaquin Valley. He would spend the late 1960s and 70s assisting Chávez and the UFW with various elections and boycotts, training thousands of UFW volunteers in his organizing methods. Well into the 1980s, he trained a number of groups working on a broad range of issues, from U.S. intervention in Central America to nuclear disarmament. One of his favorite axioms described the role of the organizer: “A good organizer is a social arsonist who goes around setting people on fire.”

Recruited by Saul Alinsky to become a full-time organizer, Herman Gallegos decided to pursue his career in social work and received his Masters in Social Work (MSW) from U.C. Berkeley, becoming an advocate for Chicano youth and active in the local CSO. After graduation, Gallegos worked as a district director with the San Bernardino County Council of Community Services, a social planning demonstration project supported by the Rosenberg Foundation. In 1965, Gallegos, Dr. Ernesto Galarza, and Dr. Julian Samora were recruited by the Ford Foundation to serve as national affairs consultants. The group explored potential philanthropic support, making recommendations and identifying solutions to address the growing needs of Latino communities. Gallegos went on to become executive director of the National Council of La Raza in 1968, co-founder of Hispanics in Philanthropy, and a U.S. public delegate to the 49th General Assembly of the United Nations.

César Chávez left the CSO because of its emphasis on urban social justice issues. In 1962 he and Dolores Huerta co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (later the United Farm Workers of America). Chávez believed it was important that the new union succeed through nonviolent tactics (boycotts, pickets, and strikes). Although Chávez’s methods as an organizer and labor leader were sometimes controversial, the movement he led brought farmworkers dignity and self-respect, as well as better wages and working conditions. In California, he pushed through what remains today the most pro-labor law in the country, the Agricultural Labor Relations Act, granting farm workers the right to organize and petition for union elections. As stated in the César Chávez Special Resource Study, issued by the National Park Service in 2012: “César Chávez is recognized for his achievements as the charismatic leader of the farm labor movement and the United Farm Workers of America (UFW), the first permanent agricultural labor union in the history of the United States. The most important Latino leader in the U.S. during the twentieth century, Chávez emerged as a civil rights leader among Latinos during the 1950s. Moreover, Chávez and the UFW sought to inspire all men and women to respect the dignity of labor, the importance of community, and the power of peaceful protest.“

The legacy of these organizers from an earlier time can be seen in the work of a generation of activists and community organizers who joined the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement during the 1960s and '70s, transforming their lives and inspiring the activism that continues through today.

Mexican Farm Worker Unionization, 1930-1960

During the Great Depression, ethnic Mexicans viewed labor organizing campaigns as part of the promise of equality and civil rights. During this time, Santa Clara County saw some of the most significant agricultural strikes in the U.S., many involving Mexican workers. Before WWII, most Mexicans worked on farms in the fruit and nut orchards or tomato and pea field/row crops. The Depression of the 1930s saw a deterioration in working conditions and a dramatic decrease in pay for orchard and field workers, who were paid by piece work rather than hourly wages. Historian Glenna Matthews claims that weekly pay dropped from $16.33 in 1929 to $8.04 in 1933. Growers stopped working cooperatively in the fruit exchange and began selling their crops individually, competing with each other and lowering wages even further. During the New Deal, between 1933 to 1937, the federal government supported farmers by buying their crops, thus propping up prices.

In 1931 the new Cannery and Agricultural Workers Industrial Union (CAWIU) set up its state headquarters in San José at 81 Post Street, charging monthly dues of twenty-five cents for the employed and five cents for the unemployed. Dorothy Ray Healey, Elizabeth Nicholas, Pat Chambers, and Caroline Decker were among the CAWIU organizers working in the county. The CAWIU undertook thirty-seven agricultural strikes in California. Historian Glenna Matthews contends that Santa Clara County, as in the rest of the nation, saw more strikes and violence in 1933 than ever before, with three agricultural strikes and one brutal non-agricultural-related lynching.

In April of 1933, 2,000-3,000 pea pickers, composed of Mexicans and Dust Bowl migrants working near the Milpitas/De Coto County line, struck for higher wages and lost. In June 1,000 cherry pickers, mostly Spanish workers from the Mountain View area, struck for higher wages. That same year, the cherry picker strike was considered the most violent of the three strikes in Santa Clara County. Workers were successful and won a 50-percent raise, from twenty cents to thirty cents an hour. According to the La Follette Civil Liberties Committee Report (1936-1941), the cherry pickers were successful because the Spanish workers were homeowners and had invested in their communities, unlike the migrant Mexican and Dust Bowl pea pickers.

In August 1933 pear pickers staged a strike, CAWIU’s most successful strike in the County, largely due to organizer Caroline Decker, who gained the support of the Palo Alto Democratic Club. In turn the Democratic Club, state and federal government officials, and the California Bureau of Labor Statistics backed the union’s right to picket, opposing the growers who had obtained an injunction against picketing workers.

The Bracero Program made it difficult to organize farmworkers throughout the Southwest, as well as Santa Clara County, because braceros were used as strikebreakers until the program ended in 1964. Ernesto Galarza organized agricultural strikes (though not in Santa Clara County) using the National Farm Labor Union during the 1940s and 1950s.

In 1937, workers in thirteen dried fruit companies decided to unionize. They organized the Field Practice Group and initially contracted with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), considered a “company union” less concerned with non-white members, who represented 98% of the dried fruit workers of Santa Clara County. Unlike cannery workers, in 1941 dried fruit workers left the AFL and voted for representation from the more left-wing CIO, which promoted for the largely Mexican workforce higher wages, retirement benefits, and a hiring hall instead of a shape up.

Title: Mexican grandmother of migrant family picking tomatoes in commercial field. Santa Clara County, California

Creator(s): Lange, Dorothea, photographer

Date Created/Published: 1938 Nov.

Rights Advisory: No known restrictions.

Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Collections: Farm Security Administration/Office of War Info. Black-and-White Negatives

Part of: Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection

Permalink: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2017770799/

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

Mexican Cannery Worker Unionization, 1917-1960

The first Santa Clara County cannery strikes took place in 1917 with the AFL’s Toilers of the World. According to historian Glenna Matthews, the Toilers signed a two-year contract that only benefitted male workers. Not until the 1930s did women cannery workers find a union voice.

Initially, cannery and field/orchard work were seen as components of the larger agriculture industry and excluded from government-sponsored protections afforded to industrial workers under the 1935 National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) or The Wagner Act. By the 1930s, as more mechanization was introduced, cannery and packinghouse labor gained protections offered to industrial workers. According to historian Glenna Matthews, canners strengthened their efforts to fight unionization during the 1930s with the formation of the Canners’ League. The 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act stipulated that competing companies within an industry should cooperate, which the fractured growers resisted.

During the Great Depression, Santa Clara County canners faced a harsh economic future. Profit margins were dropping, executives took pay cuts, and small canners went out of business. According to historian Glenna Matthews, during that decade CalPak reduced production by one third. Processors tried to reduce expenses by lowering workers’ pay.

With the first dramatic decrease in wages, in 1931 cannery workers fought back with their first strike under the Cannery Agricultural Workers Industrial Union (CAWIU). Dorothy Ray Healey and Elizabeth Nicholas were among the organizers, with Dorothy taking the lead with cannery workers. A few months prior to this strike, Italian and Spanish cannery workers formed the American Labor Union and revealed the harsh conditions cannery workers faced. In 1931 the CAWIU set up picket lines at several canneries. Workers were arrested, and in July 2,000 workers held a rally in St. James Park, demanding that police release jailed picketers and triggering the worst riot in San José history. In response Richmond-Chase cannery set up machine guns at its gate, and CalPak threatened to ship its fruit to distant canneries. The strike was lost, and the CAWIU shifted its focus to unionizing agricultural workers.

The 1931 cannery strike developed future cannery union leaders who joined the struggle for worker representation led by the American Federation of Labor (AFL). The AFL was seen as a “company union,” not taking the grievances of cannery workers seriously, particularly those of Mexican women. At the end of the 1930s, the AFL battled the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) for cannery worker representation and won the struggle. By the end of the 1930s, all San José canneries were unionized and remained so until the last one, Del Monte Plant #3, closed in the 1990s, with union representation shifting back and forth. In 1945 the AFL relinquished its control of Santa Clara County cannery workers to the Teamsters, who neglected the rights of non-white cannery workers. Union representation returned to the AFL, which merged with the more left-wing CIO in 1955. By the 1950s many Mexican cannery workers had gained unemployment insurance, a livable wage, and benefits for the first time. In 1967 under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, jobs could no longer be classified as “male” or “female,” so women could enter the more lucrative warehouse jobs previously controlled by men. Through the unions, Mexicans were able to earn the salaries needed to settle permanently in the colonias and become homeowners.

Title: Women Strikers at CalPak Plant #9 [California Packing Corporation Pickle Plant. became Del Monte, located at Jackson and N. Seventh Streets, San José]

Date: c. 1931

No: ECS1770

Collection: Edith C. Smith Collection

Source: Sourisseau Academy

- Remote video URL

Ernesto Galarza’s Background

Dr. Ernesto Galarza was born in 1905 in the village of Jalcocotán near Tepic, Nayarit, México. In 1911, he came to the U.S. with his mother and uncles to escape the Mexican Revolution. After losing his mother and uncle to influenza, Galarza lived in the Sacramento barrio working as a farm laborer. His surviving uncle made it possible for him to continue his education. At age eight, he knew more English than the adults in the labor camp and became a spokesman for them, highlighting their poor living conditions. Galarza understood that education was essential and to finance his schooling, took jobs as a messenger, clerk, court interpreter, and field and cannery worker. He would later chronicle his childhood in the autobiographical novel Barrio Boy, published in 1971.

Encouraged by his teachers, Galarza entered Occidental College in Los Angeles on a scholarship in 1923. After completing his B.A., he obtained an M.A. in history from Stanford University and then in 1944 a Ph.D. in economics from Columbia University. While at Columbia, Galarza worked for the Pan-American Union (1936-1947), serving as chief of the Division of Labor and Social Information. Although he left this job to become a labor organizer, Galarza was viewed as an intellectual and scholar whose weapons were words. Recognized as a poet, author, and educator in his later life, he taught at every level from elementary school to university and was a lifelong advocate for bilingual education.

Title: Ernesto Galarza and wife Ann

Date: 1989

Location: Series II, Box 6, Folder 3

Collection: Ted Shl Archives

Source: Special Collections, SJSU Library

Ernesto Galarza NFLU and The Bracero Program

Through his research, Galarza came to understand that one of the major obstacles to unionizing Mexican farmworkers was the 1942 Mexican Farm Labor Program Agreement, better known as the Bracero Program. He left the Pan-American Union outraged by their acceptance of U.S. corporations’ exploitation of Mexican labor. In 1947 he became the director of research and education in California for the AFL-CIO’s National Farm Labor Union (NFLU) previously known as the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, which included black and white tenant farmers and agricultural laborers who organized for better wages, working conditions, and favorable legislation for small-scale farmworkers. In 1948 Galarza became vice president of the NFLU and was deeply involved in over a dozen unsuccessful strikes between 1947-1954, including tomato pickers in Tracy, cantaloupe pickers in Imperial County, and at the DiGiorgio Fruit Corporation. Outside of California, he organized sugar cane workers and strawberry pickers in Louisiana.

In 1952 NFLU became the National Agricultural Workers Union (NAWU), and Galarza became its secretary from 1954-1963. Strikes were impossible to win because braceros would replace strikers as strikebreakers, and Galarza left labor organizing determined to use his writing skills as a weapon to help end the Bracero Program.

Galarza had visited bracero camps and saw firsthand how employers used braceros to break strikes and avoid union organizing. Bracero labor also depressed wages for American workers. Galarza exposed abuses within the Bracero Program in his best-known work, Merchants of Labor (1964), which helped to end the program and laid the groundwork for César Chávez to begin the United Farm Workers of America (UFWA) in 1965.

Galarza became a labor organizer because he believed that to achieve civil rights, Mexican Americans and labor unions needed to work together to address workplace and community problems. Between 1963-1964, Galarza served as advisor to the U.S. House Committee on Education and Labor. In 1979, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature for his writing on braceros.

Title: NFLU Leadership c. 1940s

Collection and No: Ernesto Galarza Papers

Source:: Special Collections, Greene Library, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

Legal Challenges to Segregation

School segregation was a major issue for Mexicans in California and Texas. Groups of parents filed numerous lawsuits to push local governments to integrate local schools. These struggles united parent groups and LULAC (The League of United Latin American Citizens), and together they fought landmark cases such as Del Rio ISD v. Salvatierra in Texas (1930) and Roberto Alvarez v. the Board of Trustees of the Lemon Grove School District, often referred to as “The Lemon Grove Incident,” in San Diego, California (1931).

LULAC, the first national Mexican American Civil Rights organization, was established in 1929 by American citizens of Mexican descent in Corpus Christi, Texas. Until WWII, LULAC undertook several school desegregation court cases in Texas and California using the argument that Mexicans were white. Accordingly, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) gave American citizenship to Mexicans living in the U.S. territory at the end of the Mexican American War while the U.S.Constitution had stipulated that only white males were eligible for U.S. citizenship. This legal argument was not successful.

After WWII, LULAC worked with the Mexican consulate and the NAACP to strategize for Mendez v. Westminster (1947). This California Supreme Court case repealed all segregation in California schools, arguing that the 14th Amendment provided for “equal protection” under the law, and influenced the landmark 1954 U.S. Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education Topeka, Kansas. In 1954, lawyers from the American G.I. Forum and LULAC argued in the U.S. Supreme Court case of Hernandez v. Texas that the Mexican American defendant was denied “equal protection” under the 14th Amendment. The court granted that Mexican Americans were “a class apart,” not easily fitting into a legal structure that only recognized blacks and whites. Direct action on segregation, including strikes, walkouts, and boycotts, would come much later.

Title: Mayfair School Class Portrait with Christmas Tree, c. 1940

Date: 1935-1950

Collection: History San José Online Catalog

Owning Institution: History San José Research Library

Source: Calisphere

Permalink: https://calisphere.org/item/ac5699114d7befb729677d8c6cae3988/

The League of United Latin-American Citizens: A Texas-Mexican Civic Organization

Jan. 5, 1931: Lemon Grove Incident - Zinn Education Project

Background - Mendez v. Westminster Re-Enactment | United States Courts

April 14, 1947: Mendez v. Westminster Court Ruling - Zinn Education Project

Mendez v. Westminster School District | National Archives

American Latino Theme Study: Education (U.S. National Park Service)

The American G.I. Forum

WWII brought a new awareness of racial issues as the military began to integrate under Executive Orders in 1941 and 1948, though full integration would not come until 1960 for some branches. Anglo American GIs shared bunkrooms, meals, and social time with their Mexican counterparts and understood that they had to rely on one another in combat. Although Mexican Americans did not face the same level of segregation in the military as African Americans and lighter skinned Mexicans were sometimes classified as white, they understood that racial prejudice still remained.

As Mexican veterans returned home, they continued the fight for the “Double V for Victory”–victory against racism abroad and at home. When Mexican American veterans were banned from participating in local veterans’ groups and denied services at veterans’ hospitals or military cemeteries, in 1948 they formed the American G.I. Forum, which welcomed all veterans of color.

The GI Forum was founded in Texas by Dr. Hector P. García to fight discrimination against Mexican Americans in employment, education, and access to veterans’ benefits. The organization gained national attention when it took up the Felix Longoria case in 1949. Longoria, an ethnic Mexican veteran from Texas killed in the Philippines, was refused burial in his hometown, Three Rivers, Texas. The GI Forum appealed to then-Senator Lyndon Baines Johnson, who had seen discrimination first hand in Texas after teaching in a segregated school for Mexican Americans. In the Longoria case, Johnson intervened, arranging for him to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors at no cost to his family.

The San José chapter of the Forum was formed in 1949, focusing on youth issues and offering scholarships. In 1960, the Forum collaborated with other groups, such as the Community Service Organization (CSO), on voter registration campaigns and advocating for ethnic, minority and disenfranchised communities.

Title: Conrado Barrientos US Air Force, WWII

Collection: Before Silicon Valley Project Archives, Barrientos Collection

Owning Institution: Special Collections, San Jose State University

Fr “Mac” McDonnell and Guadalupe Church

Father Donald McDonnell was a member of a group of Catholic priests, the “Spanish Mission Band,” who worked with Mexican farmworker communities. Initially Fr. McDonald served at St. Joseph Church in the Mountain View colonia (1947-1951), encouraging the formation of Club Estrella as well as a community credit union. In 1952 he moved to Eastside San José and introduced parishioners to non-violent community organizing strategies, urging them to address racial discrimination through action. Known as “Father Mac,” he was familiar with Ernesto Galarza’s writings and agricultural union organizing, and instructed parishioners on labor law, focusing on abuses of the Bracero Program.

The Eastside had no Catholic church to serve the growing Mexican population, and Father Mac helped parishioners to establish the Guadalupe Chapel. In 1953, the Catholic Church purchased an old church building, disassembled it, and moved it to the Mayfair district. It was reconstructed by parish volunteers, including siblings César and Richard Chávez and their sister Rita Chávez Medina. The building housed the growing Our Lady of Guadalupe congregation until it was replaced in 1968. The chapel also served as the first headquarters of the San José chapter of the Community Service Organization (CSO), which trained community organizers and conducted campaigns for social justice and labor rights. Because of this history, Fr. McDonnell Hall, originally the Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel, is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places (2016) and became a National Historic Landmark in 2017.

Filename: Guadalupe Mission, c. late 1950s. Cropped-Guadalupe Church Photo Album-Chavez Photos-7595.tif

Collection: Before Silicon Valley Project Archives, Guadalupe Church Photo Album

Owning Institution: Special Collections, San Jose State University (after Sept 30, 2023)

The CSO and Fred Ross

According to historian Gabriel Thompson, Fred Ross, Sr., was born to an affluent and politically conservative family from Los Angeles. He attended the University of Southern California, where he was exposed to politically liberal ideas. Ross wanted to be a teacher, but after his graduation in 1936, due to the Depression, he took a three-year term as a relief worker. He then became manager of the federally-funded Farm Security Administration (FSA) Arvin Migratory Camp for Dust Bowl migrants located near Bakersfield. He replaced the previous corrupt manager and tried to regain the workers’ confidence by forming a workers’ council and supporting a cotton strike. During his time at Arvin Camp, he met folk singer Woody Guthrie and listened to his songs of political protest.

During WWII Ross worked for the War Relocation Authority in Cleveland, finding jobs and housing for Japanese Americans not placed in internment camps. After WWII, he returned to Los Angeles to work for the American Council on Race Relations, organizing “multi-racial unity leagues.” He led voter registration drives to force out racist local politicians and desegregate schools. His work contributed to the successful 1948 California State Supreme Court decision in Mendez v. Westminster. Ross also worked for Saul Alinsky’s Chicago-based Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF). In 1947 he was hired to promote Latino political power in Los Angeles.

That same year, in Boyle Heights, a Los Angeles neighborhood with a large Mexican population, Ross formed the first chapter of the Community Service Organization (CSO), which was established to protect the civil rights of Mexican Americans and foster political and civic engagement. Fred Ross approached social worker Edward Roybal and Antonio Rios, a union organizer with the United Steelworkers of America, with the idea of forming a community-based organization. In the IAF model, an outside organizer works with local leaders to create a democratic organization where people can identify their concerns and address them through direct action. Edward Roybal became the first president and main spokesman of the CSO’s LA Chapter.

Building on the earlier work of mutualistas, church groups, and community associations, the CSO stressed voter registration and held citizenship classes to promote political involvement. They also addressed ongoing problems such as poor community services and discrimination in housing, education, and employment. After WWII, Mexican American and African American civil rights groups occasionally worked together, though they sometimes differed in their aims and goals. For example, education was an important issue for both groups, but bilingual education was extremely important to Mexican Americans, while busing was a higher priority for African Americans. Fair housing and employment legislation were key issues for both, but Mexicans prioritized pensions for resident non-citizens, who were often not eligible for social services.

CSO members learned the importance of becoming activists in their own communities. By 1963, the CSO had 34 chapters across the Southwest, registering 500,000 new voters and helping over 50,000 Mexican immigrants obtain citizenship in California. In 1949, utilizing the community organizing skills of Fred Ross, Sr., and CSO volunteers, Edward Roybal was elected to the Los Angeles City Council. The first Mexican to win a seat since 1881, Roybal was later elected to Congress, serving from 1963 to 1993.

Title: Fred Ross, 1950s

Collections: Fred Ross Papers

Source: Special Collections, Greene Library, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, CA

The Formation of the San José Chapter of the CSO

In 1951 San José State College sociology professor and American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) member Claude Settles brought Fred Ross, Sr., to campus to give a lecture. Herman Gallegos, a student, and Leonard Ramirez and public health nurse Alicia Hernández, two community members, attended that lecture and encouraged Ross to organize a new CSO chapter in the barrio known as “Sal Sí Puedes“ (meaning “Get Out if You Can,” a name that can be traced back to a Mexican land grant) in the Mayfair district of East San José.

Assigned to a project in Kansas City, Ross reached out to his contacts in Santa Clara to provide local assistance and support. One of these was Quaker philanthropist and AFSC member Josephine Duveneck of Los Altos Hills. Duveneck initially provided housing for Fred Ross, Sr., a place to hold meetings, and financial support. In 1952 Ross was assigned by Saul Alinsky to work in San José, and shortly upon arrival, he sought out Father McDonnell to help identify potential organizers, such as Guadalupe-parish member César Chávez.

Ross’s community organizing techniques were based on door-to-door canvassing and house meetings. Volunteers such as Rita Chávez Medina (César’s sister), Herman Gallegos, and César Chávez went door-to-door in the Eastside’s crowded neighborhoods, over unpaved streets, registering voters and talking to residents about how to form a CSO Chapter. The community was ready, and the formational meeting took place at Mayfair Elementary School in 1952. Meetings were later moved to the Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel, where the CSO established its first offices, local campaigns were planned and organized, and volunteers were trained.

Filename: FAIR USE_HSJ The Weekly Mayfair_Flooding East Side_Jan 17 1952_CROP_2006791.jpg

Objectid: 2006-79-1

Caption: Mayfair_19520117_p01

Owning Institution: History San Jose

Permalink: https://historysanjose.pastperfectonline.com/media/947D46E1-8C99-4AA2-B387-450801468900

The Founding Members of the CSO San José Chapter, Excluding Cesar Chavez

The following are some of the founding members of the CSO San José Chapter:

Herman Gallegos became the first president of the San José Chapter as well as president of the national CSO in 1960. Gallegos grew up in a poor coal-mining family who lived in a mud hut built by his father near the mines in Ludlow, Colorado, where he observed the infamous “Ludlow Massacre” of striking workers. After the massacre, the family moved to San Francisco. Gallegos first attended San Francisco State University, where two of his professors, Dr. John Beecher and Dr. Herbert Bisno, refused to sign a loyalty oath required under the Levering Act affirming that the signer was an American and not a Communist or risk being fired. When a state police officer came into the classroom and handed Dr. Beecher a letter requiring him to leave, Gallegos and two Jewish students walked out of class and went to the administration office demanding the professor be reinstated. Because the protesting students did not have a permit, the police broke up the protest, and Gallegos decided to transfer to the Social Work Program at San José State College. When he joined the CSO, he was attending college, living on the Eastside, and working as a gas station attendant. At that time he and Hernández were the only two members of the organization with a college education. In 1960 Gallegos became national CSO president, with César Chávez serving as executive director.

Alicia Hernández, a public health nurse who worked with families on the Eastside, became a founding member after attending Fred Ross’ first talk at San José State College (with Herman Gallegos, Juan Marcoida, and Leonard Ramierez). She became the first temporary chair or interim president of the CSO San José chapter. A friend of Chávez’ wife Helen, Hernández arranged the first meeting between Ross and César Chávez, who was 25 years old. Hernández and Chávez walked door to door in the Eastside registering voters.

Juan Marcoida, another student who heard Ross’s initial talk at San José State, was an engineer who worked by day and went to college at night. He became a founding member of the CSO San José Chapter while working at the General Electric Plant, where he’d been employed since its opening in 1947. A resident of Sal Sí Puedes in the Eastside, Marcoida served two terms as president of the CSO San José Chapter. He also hosted a radio program called CSO INFORME that aired for ten years on KLOK and KSJO radio stations, highlighting jobs, legal issues, police brutality, domestic abuse, immigration, deportation, scams, and voter registration assistance. He was named “1956 Man of the Year” in El Excentrico magazine.

Rita Chávez Medina, the eldest of the Chávez siblings, had quit school at age 12 to help support the family after they lost their farm. She continued to work in the fields, transitioning into cannery work when she married and her family moved to San José. There she became active in local efforts to obtain a Catholic church to serve the Mexican community in the Eastside, enlisting the help of her brothers César and Richard, a union carpenter. She had already demonstrated her organizing skills in the church campaign when César asked her to work on the CSO voter registration drive, and he increasingly delegated local organizing tasks to her. Rita rose to become CSO San José Chapter President.

Leonard Ramirez, who also heard Ross’ speech, and his wife Erma became founding members of the CSO San José Chapter, fighting for paved streets and street lighting as well as promoting voter registration. Ramirez led the CSO drive to abolish citizenship requirements to receive Social Security benefits for old age. The law was revised in 1960 taking out Social Securities citizenship requirement. Ramirez was born in Watts, California, in 1926. After high school, he joined the army during WWII. Through the help of the GI Bill, he graduated from San José State College in 1953, one of only five Mexican students attending the university.

Filename: FAIR USE_HSJ The Weekly Mayfair_Flooding East Side_Jan 17 1952_CROP_2006791.jpg

Objectid: 2006-79-1

Caption: Mayfair_19520117_p01

Owning Institution: History San Jose

Permalink: https://historysanjose.pastperfectonline.com/media/947D46E1-8C99-4AA2-B387-450801468900

The Background, Recruitment and Rise of César Chávez to the CSO

César Chávez was born in 1927, the second of six children in an extended family of devout Catholics, and grew up on his grandparents’ family farm near Yuma, Arizona. In 1939, during the Depression, the farm was auctioned and sold to cover back taxes. César’s father had been diagnosed with a lung disease requiring a move to a cooler climate, and the family joined the growing number of American migrant workers in California. Unlike sister Rita, who quit school at 12 years of age to work in the fields full time, Césario (César) carried family expectations as the eldest boy and was allowed to attend school while working in the fields weekends and holidays. Eventually, he and his family worked across California from Brawley to Oxnard, Atascadero, Gonzales, King City, Salinas, McFarland, Delano, Wasco, Selma, Kingsburg, and Mendota. The essential injustice and underlying racism the family experienced during those years made a strong impression on César. Despite the numerous interruptions to his education, he graduated from the eighth grade in June 1942 and became a full-time farm laborer until he joined the Navy in 1945.

A Navy veteran by 1947, Chávez returned to working with the family as an agricultural laborer. He joined the National Farm Labor Union (NFLU), picking cotton in Corcoran, near Delano. Cesar and his brother Richard both worked briefly in the lumber yards of Crescent City. However, the distance was too far from the rest of the family in San José, so by the 1950s, their sister Rita encouraged César and Richard to relocate their families to San José. Richard became a successful union carpenter, and César continued working in the fields and local lumber yards when, at 25 years of age, he met Fred Ross, Sr., in 1952.

When Ross had begun to look for local organizers for the CSO, Alicia Hernández offered to introduce him to her friend Helen Chávez and her husband César, who had become active in social justice work through his association with Father McDonnell, pastor of the Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel. Through Fr. McDonnell, Chávez had learned the principles of nonviolent resistance and been introduced to Catholic teachings that emphasized social justice and challenged economic and social inequalities. With Father Mac, Chávez had visited labor camps and farmworkers living beyond the Eastside.

Fred Ross encouraged Chávez to become a full-time paid organizer for the Community Services Organization (CSO), and he soon began setting up chapters in the Bay Area and other towns across the state. Named executive director of the national CSO in 1959, Chávez moved to Los Angeles to work in the organization's main office. Though the CSO had become a successful advocate for communities of color, Chávez had not given up the idea of working with farmworkers and felt that the CSO was more focused on the problems of urban communities. In 1962 he left the CSO and moved to Delano, California, with his wife, their eight children, brother Richard Chávez, and Dolores Huerta, another CSO colleague from Stockton, in order to establish a union for farm laborers, the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA)

Filename: FAIR USE_HSJ The Weekly Mayfair_Flooding East Side_Jan 17 1952_CROP_2006791.jpg

Objectid: 2006-79-1

Caption: Mayfair_19520117_p01

Owning Institution: History San Jose

Permalink: https://historysanjose.pastperfectonline.com/media/947D46E1-8C99-4AA2-B387-450801468900

CSO San José Chapter Organizing Tactics

In San José, CSO organizers held house meetings where they identified community concerns, which became the focus of their campaigns, and recruited potential members and volunteers. Formal meetings were then held at the Mayfair School to create an official organization. The main issues of concern to Eastside residents included improving essential services, paving streets, installing streetlights, dealing with police brutality, and addressing economic inequality. Due to the anti-communist fervor of the early 1950s, it was important to involve religious leaders like Fr. McDonnell to assure the authorities that CSO members were not Communists or political agitators, so the opportunity to hold regular meetings at the Chapel was welcomed.

Articles in El Excentrico introduced more people to the organization and emphasized its roots in the local community. Juan Marcoida, CSO member and chapter president, hosted a radio program, CSO INFORME, for ten years on KLOK and KSJO radio stations, with businesses donating to cover airtime costs. CSO services were provided free of charge, and, with so many people in need of help, fundraising was continuous–donated Christmas trees and tamales were sold, musicians played for free at dances, and members held raffles and ran a secondhand store.

Prior to World War II, only a small percentage of Mexican immigrants had filed naturalization papers since citizenship did not appear to improve their working or living conditions. CSO members learned that some problems required legislative remedies to develop better public policy, which made citizenship, and thus citizenship classes, more important. The CSO became part of a civil-rights coalition, including the NAACP, the Urban League, the Jewish Community Relations Committee, the Japanese American Citizens League, and other organizations that met regularly to frame the strategy for public policy involvement in California. By increasing their political power through citizenship classes and voter registration, these groups fought discrimination in education, housing, and employment on local and state levels. In the 1950s, the CSO San José Chapter lobbied to end citizenship requirements for Social Security benefits and promoted voter registration drives with the assistance of the G.I. Forum and worked with the NAACP to challenge discrimination of Mexicans against African Americans.

Filename: FAIR USE_HSJ The Weekly Mayfair_Flooding East Side_Jan 17 1952_CROP_2006791.jpg

Objectid: 2006-79-1

Caption: Mayfair_19520117_p01

Owning Institution: History San Jose

Permalink: https://historysanjose.pastperfectonline.com/media/947D46E1-8C99-4AA2-B387-450801468900

Life After the CSO: Some of the Founding Leaders of the San José Chapter

Alicia Hernandez, who did not like being in the spotlight that can accompany a leadership role, moved to San Francisco to continue nursing.

Leonard Ramierez became a probation officer and helped to open the James Ranch Juvenile facility in Morgan Hill (William F. James Boys Ranch). He became chair of the United Way of Santa Clara County, a founder of the Hispanic Development Corporation, and a member of the GI Forum.

After leaving the CSO in the early 1960s, Fred Ross helped organize residents of Guadalupe, Arizona, primarily Mexican Americans and Yaqui Indians, to gain basic services such as paved roads and stop signs. He then taught organizing skills to students at Syracuse University working on a campaign, supported by federal “War on Poverty'' funds, to organize African American residents living in dilapidated public housing. The idea of paying organizers with government funds to stir up people to challenge government policies proved controversial, and the funding was eventually halted. Returning to California in 1966, Ross became the organizing director of the United Farm Workers Association. He assisted the UFW in a campaign over who would represent workers at DiGiorgio, a major grower in the San Joaquin Valley. He would spend the late 1960s and 70s assisting Chávez and the UFW with various elections and boycotts, training thousands of UFW volunteers in his organizing methods. Well into the 1980s, he trained a number of groups working on a broad range of issues, from U.S. intervention in Central America to nuclear disarmament. One of his favorite axioms described the role of the organizer: “A good organizer is a social arsonist who goes around setting people on fire.”

Recruited by Saul Alinsky to become a full-time organizer, Herman Gallegos decided to pursue his career in social work and received his Masters in Social Work (MSW) from U.C. Berkeley, becoming an advocate for Chicano youth and active in the local CSO. After graduation, Gallegos worked as a district director with the San Bernardino County Council of Community Services, a social planning demonstration project supported by the Rosenberg Foundation. In 1965, Gallegos, Dr. Ernesto Galarza, and Dr. Julian Samora were recruited by the Ford Foundation to serve as national affairs consultants. The group explored potential philanthropic support, making recommendations and identifying solutions to address the growing needs of Latino communities. Gallegos went on to become executive director of the National Council of La Raza in 1968, co-founder of Hispanics in Philanthropy, and a U.S. public delegate to the 49th General Assembly of the United Nations.