Topic Four

The Mountain View Colonia, WWII-1960

The Hispanic roots of Mountain View stretch back to the Mexican land grant of Rancho Pastoria de Las Borregas of 8,800 acres that included lands in current Sunnyvale and Mountain View, granted to Francisco Estrada and his wife Inez in 1842. When the Estradas died in 1845 they left their land to Inez’s father, Mariano Castro. Castro sold the eastern half of the rancho, what is now Sunnyvale, to Irishman Martin Murphy, Jr. Murphy had arrived in 1844 and planted Santa Clara County’s first orchard on his newly acquired land. Castro died in 1856, leaving the Mountain View portion to his son, Crisanto Castro. Like other Mexican Californios, the Castros fought in the American courts from 1852 to 1871 to validate their land grants but lost most of it to squatters and lawyers fees. The Castro family remained in Mountain View until 1958, when they sold their remaining 23.5 acres to the City of Mountain View.

In the early 1900s Spanish immigrants arrived in Santa Clara County. Many who had worked in the orchards and canneries in the 1920s and 1930s moved to Mountain View, California, settling in the northern section of the city above the canneries, packinghouses and railroads. These included the Mountain View Fruit Packing Company, Clark Canning, and San José Fruit Preserving Company. Around 1920, the P.L. Sanguinetti Cannery in Mountain View was acquired by the Richmond-Chase Cannery, one of the largest in California.

Sharing a common language, the Spanish community welcomed Mexican immigrants who arrived in Mountain View during and after WWII. This would eventually transform the Spanish neighborhood into the Mountain View Mexican Colonia. In such a small town, Mexicans did not form a separate commercial district but melded cultural traditions and a shared language. St. Joseph Catholic Church became the heart of the Colonia, and during the late 1940s to 1950 Father Donald McDonnell encouraged the Mexican community to address their financial, economic, and social needs by creating Club Estrella as well as a community credit union. Club Estrella hosted annual church and community events for the entire Spanish speaking community. Increasing urbanization and highway expansion during the 1950s and 1960s brought major thoroughfares through the heart of the district and decimated the established Mountain View Colonia. Father McDonnell was assigned to the Mexican mission in Eastside San José in 1951, and helped establish the San José de Guadalupe Church and became a mentor to César Chávez.

Title/Caption: Father Donald McDonnell, Parish Priest in Mountain View 1947

Date: 1947

Collection: Nick Perry Family Collection

Owning Institution: Mountain View Historical Association

Source: Mountain View Public Library

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

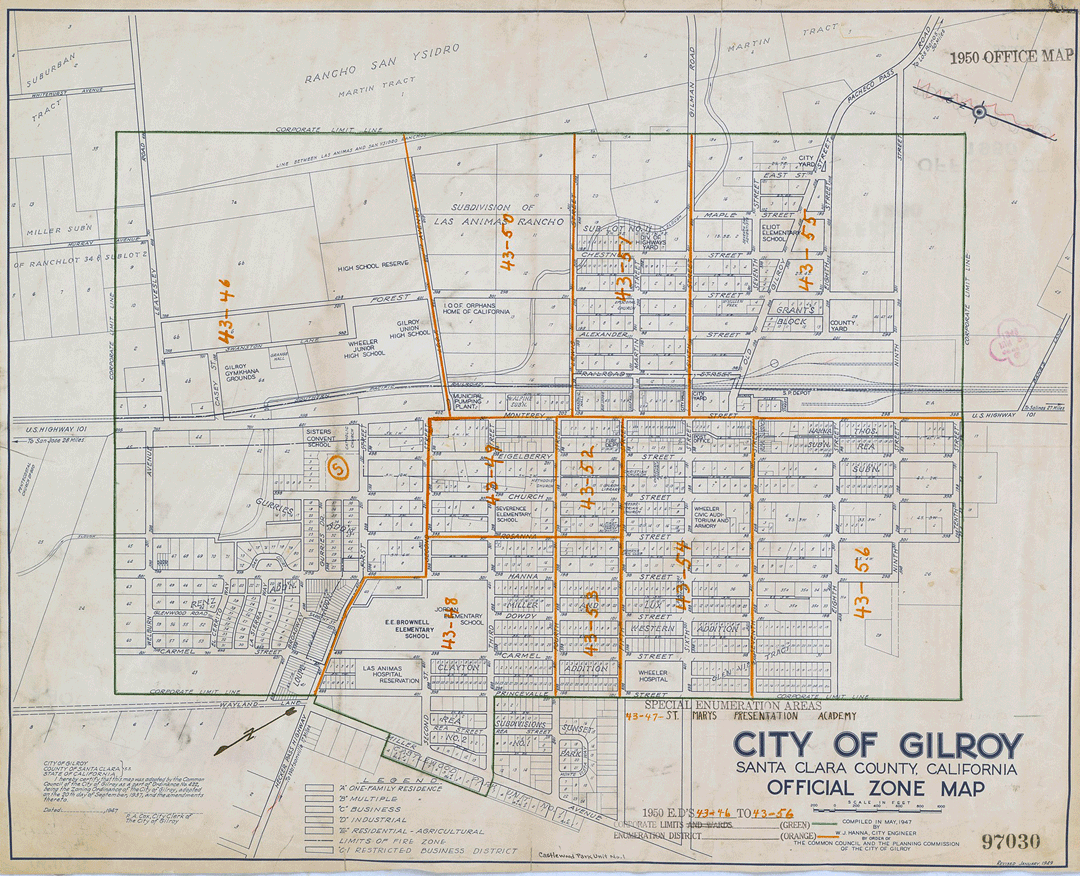

The Gilroy Colonia, WWII-1960

During the Spanish colonial era, two land grants (Rancho Las Animas and Rancho San Ysidro) comprised what is now the region known as Gilroy. Additional land grants were issued during the Mexican era. The city of Gilroy was eventually named after a Scottish immigrant, John Cameron, who came to Monterey in 1814 and changed his name to Juan Bautista Gilroy after converting to Catholicism. He worked on Rancho San Ysidro, marrying the ranchero’s daughter Maria Clara Ortega, and became a naturalized Mexican citizen. Eventually he inherited a part of Rancho San Ysidro and raised cattle. During the American Period, Gilroy incorporated as a town (1868), and most of the Mexican rancho land passed into the hands of Anglo farmers and ranchers. In the late 1850s much of Rancho Los Animas (12,000 acres) was sold to Henry Miller, a famed cattleman in the Miller & Lux Company, which lobbied for the railroad to run through Gilroy in order to facilitate their cattle raising/butchering operations. The area boasted prune, cherry, and apricot orchards, with the producer exchange Sunsweet overseeing the drying of these crops for market. In the early 1960s, orchards were replaced by row crops of tomatoes, sugar beets, and garlic.

Prior to WWII, Mexican immigrants migrated to work in the orchards and fields, living temporarily on the ranches where they worked. Some Mexicans, such as the García family who migrated from Texas, began moving into Gilroy during WWII. They initially bought a large apartment complex, the Guadalupe Apartments, on Eigelberry and 7th Street, and then opened the Post Office Market on 6th Street and Monterey Road, which they sold and then established García (card) Club in 1952 on Monterey Road between 6th and 7th Street facing the railroad. The Mexican businesses of the García family were unique. Gilroy was a small town, so there was not a separate Mexican business district, and Mexican residents did not attend separate schools or theaters. Instead Wednesday was “Mexican Night” at the Anglo-owned Strand Theater, with headliners such as Cantinflas appearing on occasion.

It was not until WWII and later that Mexicans moved into higher paid, unionized cannery work. Though still seasonal, it was flexible enough to allow workers to move to other jobs when necessary. Employment at the Felice and Perrelli Cannery (1914-1997) enabled several generations of Mexican families to establish roots in town. The Gilroy Mexican Colonia appeared south of 7th Street, with some settling on the westside of Monterey Road and the majority living east of Monterey Road next to the canneries and railroad tracks.

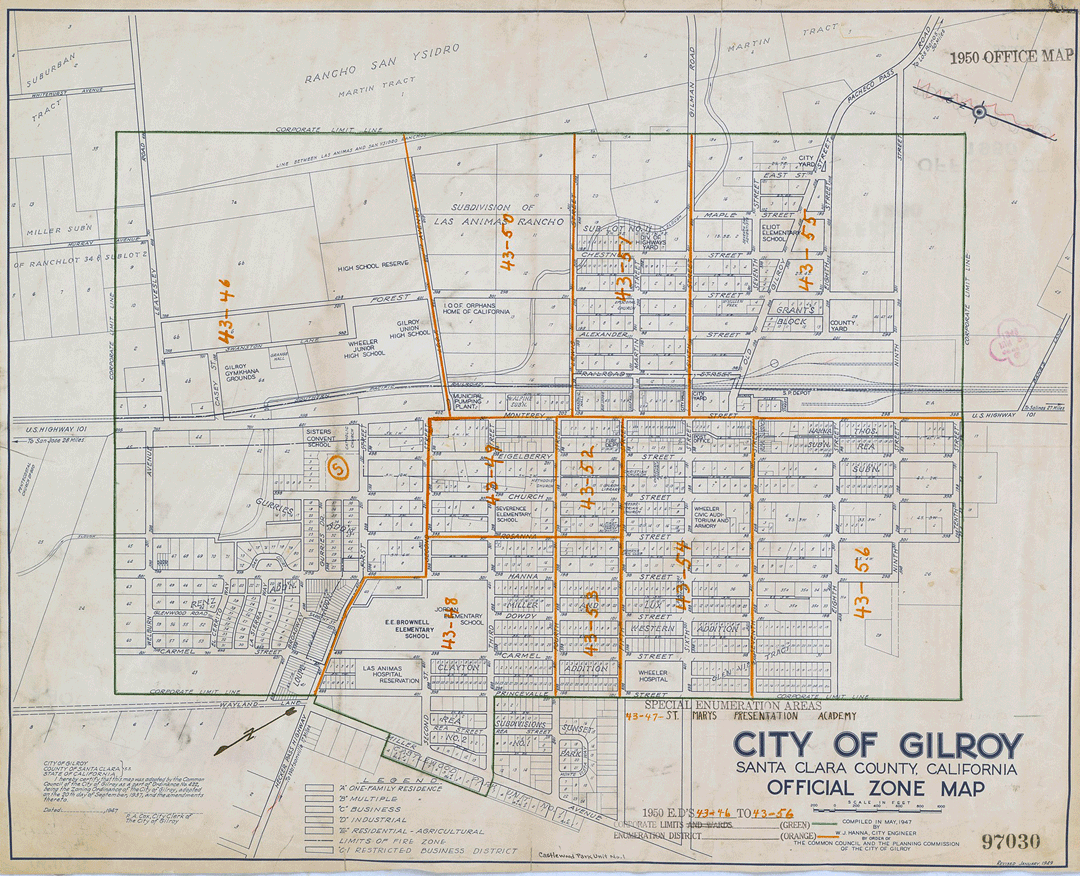

Title: Enumeration District Maps for Santa Clara County, California

Date: 1930 - 1950

Source: The U.S. National Archives

Link https://catalog.archives.gov/

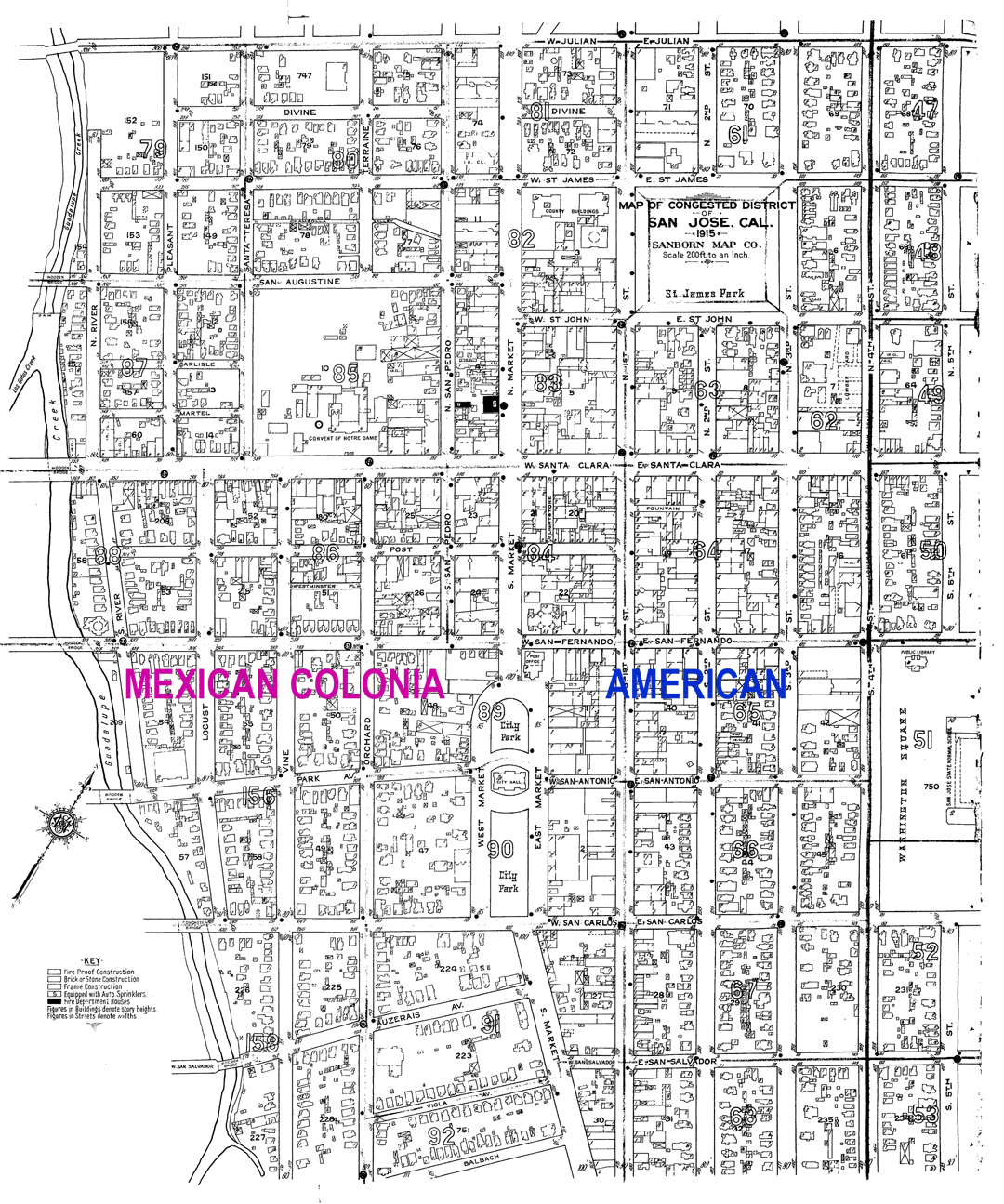

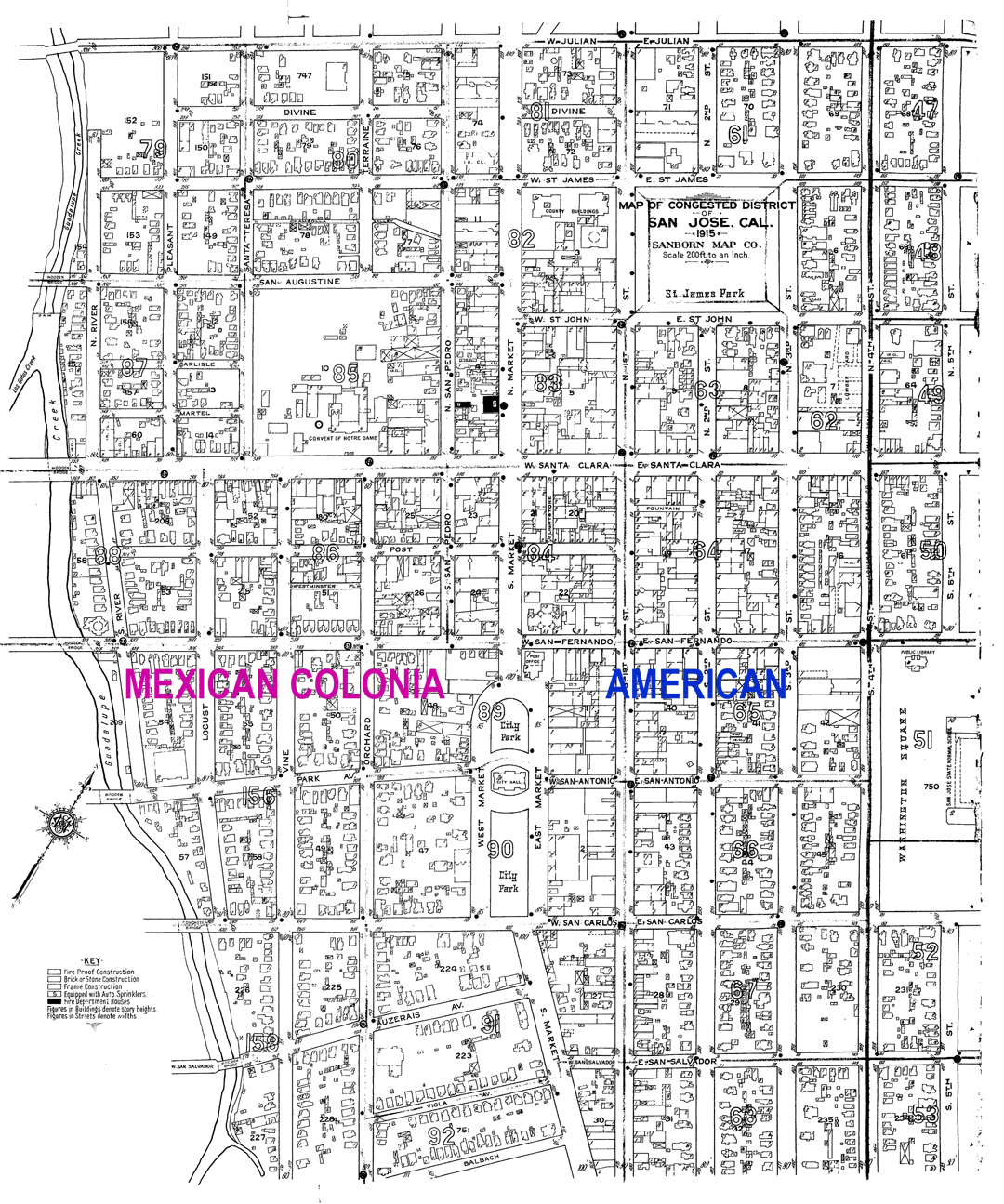

The San José Mexican Downtown Colonia Before and After WWII

As more seasonal Mexican immigrant workers arrived in the Valley, civic leaders worried that a year-round Mexican settlement would lower Anglo property values. Between 1920 and 1945, racially/ethnically restrictive covenants (land deed restrictions) and racial/ethnic redlining (lender refusal to offer loans in certain areas) on housing in cities and towns were enacted. These reinforced the segregation of Mexican colonias like San José’s old Pueblo neighborhood, located next to the less desirable industrial area filled with canneries, packing houses and railroads.

As more seasonal Mexican immigrant workers arrived in the Valley, civic leaders worried that a In 1900, Mexican and ethnically white Portuguese, Spanish and Italians resided in the Downtown Colonia. When the number of Italians moving to the old Pueblo, between the 1880s to the 1920s, expanded beyond the housing capacity, they moved into the northern, western and southern adjacent neighborhood. The southern neighborhood became known as “Goosetown”. Throughout California, Mexican colonias were pejoratively called "Mexicantowns" or "Jimtowns" (thus racially equating Mexicans to southern African Americans, who were subjected to Jim Crow laws). Historian Suzanne Guerra notes, in the 1920s, the old Pueblo, referred to by Anglo Americans as “Mexicantown”, was hemmed in by urban development and adjacent orchards resulting in fewer places to live in San José. Historian Gregorio Mora-Torres observes that by WWII, the Italian residents of the Downtown Colonia and “Goosetown” moved to other neighborhoods throughout the city. WWII also enabled ethnic Mexicans to move up to higher paying, more stable jobs in the unionized canneries, so they bought the vacated Italian homes in the Downtown Colonia.

During the 1940s, the Downtown Colonia expanded north to St. Augustine, south to San Carlos Street, and west beyond the Guadalupe River. By the late 1950s, it had reached all the way to Home/Virginia Streets. Mexicans also lived in the community north of Santa Clara Street and between Second Street and the Coyote River. This spurred the development of Mexican owned businesses downtown to serve Spanish speaking residents in the region.

Title: San José Sanborn Map 1915 annotated

Date: 1915

Collection: California Room

Owning Institution: San José Public Library

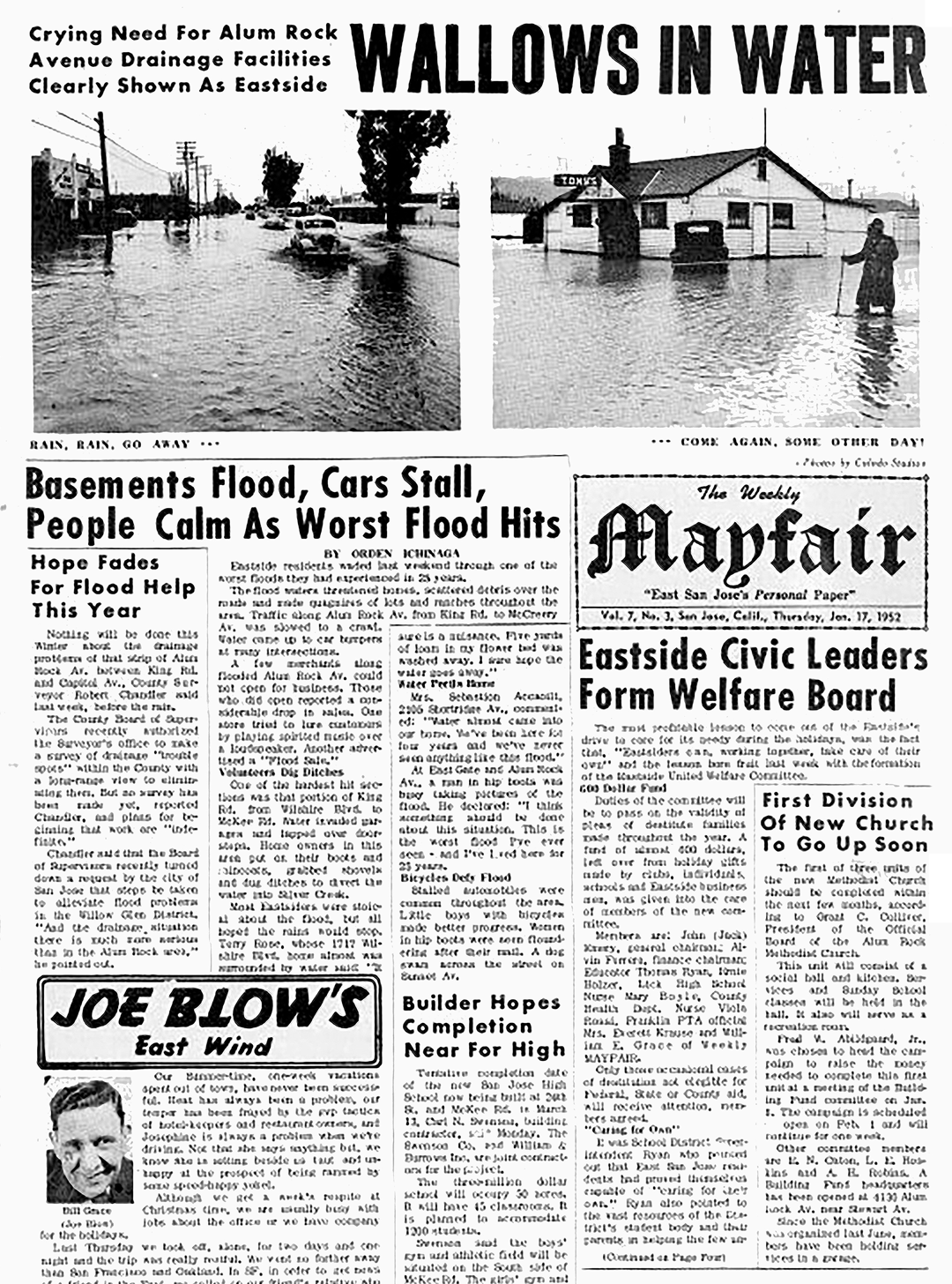

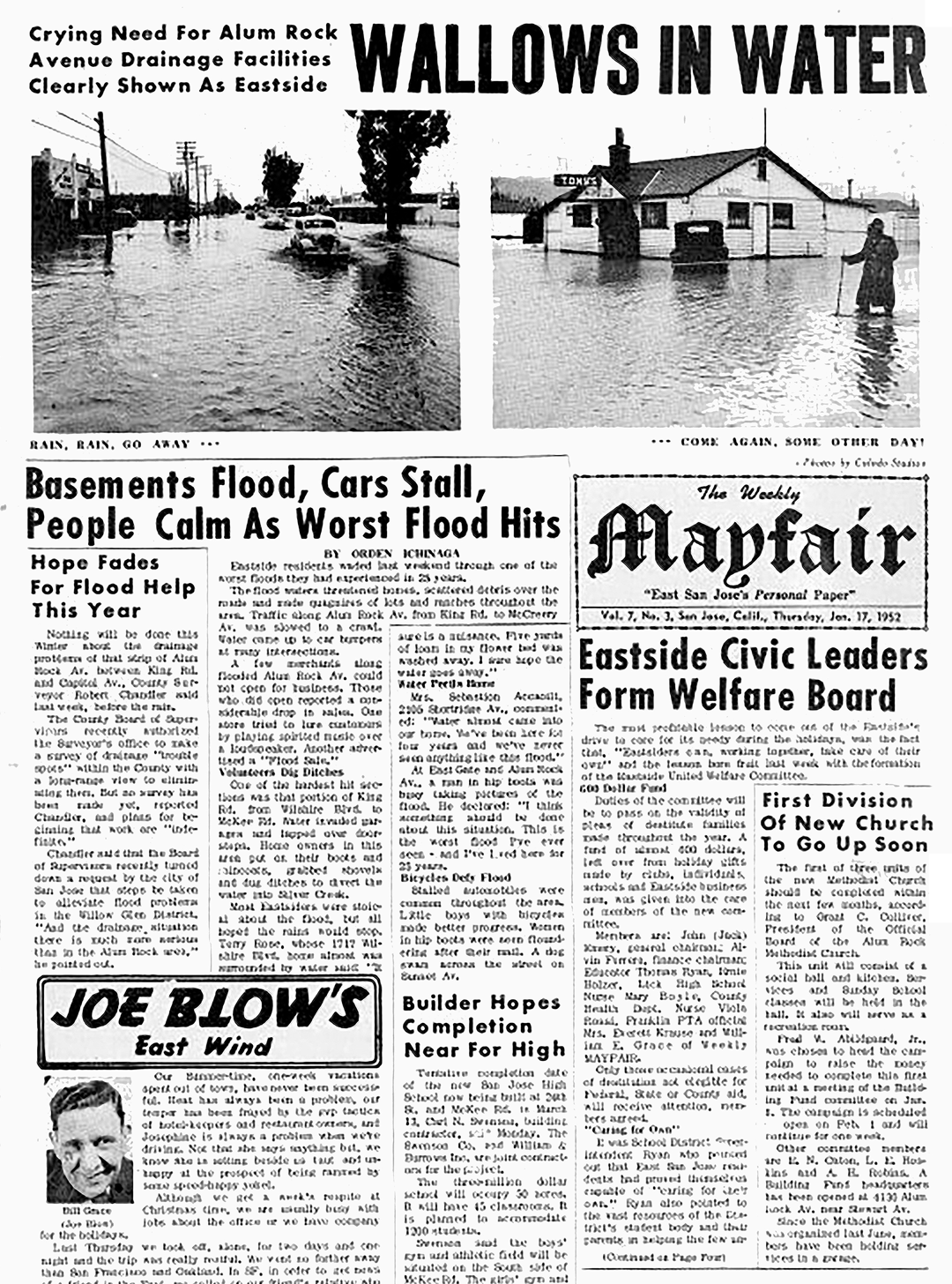

Eastside San José

The area known as the Eastside San José was first settled by Puerto Ricans, who left low-paying Hawaiian canefield jobs during WWI for higher paid agricultural work in Santa Clara County. Prior to WWII, concerned that Mexicans might move into their neighborhoods, Santa Clara County civic leaders imposed racial/ethnic restrictive covenants and endorsed redlining policies towards Mexicans. This would concentrate the Mexican populations into the Downtown Colonia or the unincorporated Eastside. Mexican migrants and exiles from the Almaden Mine joined the Eastside Puerto Rican settlement in the early 1920s. These mineworkers wanted to be near other Spanish speakers as well as cannery and farm jobs.

In 1931 the Mayfair Packing Company, for which the Mayfair District is named, was built on the Eastside and became one of eleven canneries and packing plants in San José. During WWII, ethnic whites left for higher paying munitions industry work and Mexican workers filled cannery jobs and settled there in large numbers. In 1955 the Mayfair District, nicknamed "Sal Sí Puedes" (Get Out If You Can-a name taken from an original Mexican landgrant), was home to 4,500 residents, of whom 3,000 were of Mexican descent.

The segregated Eastside provided empty lots for group camping, mobile rail housing, or long-term housing in apartments, boarding houses, and rental units. Families would often pool their money to purchase an unimproved lot where they could build their own homes. In this way, worker neighborhoods were created with a variety of owner-built housing. For decades the segregated Eastside area remained unimproved with no paved streets or street lights.

Title: The Weekly Mayfair

Collection: History San Jose Online Catalog

Owning Institution: History San José Research Library

Source: Calisphere

Permalink: https://calisphere.org/item/0653be5aee3055fe70dd9fe65b695326/

Community Segregation Policies

Similar to Southern California, ethnic Mexicans were subjected to social, residential and educational segregation throughout Santa Clara County. According to a 1950 SJSU student study and a 1978 study done by the Garden City Women’s Club, ethnic Mexicans, African Americans and Asians experienced de facto segregation in policies regarding public pools, bowling alleys, and ballrooms and dancehalls.

Santa Clara County followed California’s segregationist housing policies, which also aligned with school segregation patterns. According to California law, segregated schools were built if a community had more than ten students of Native American, Chinese, Japanese or Mongolian ancestry and if these minority students’ parents petitioned a district to build one. If the community had less than ten non-white students, these students would only be allowed to attend the community school if white parents approved. If not, then these non-white students could not attend school. Students of Mexican ancestry were not included in California’s school segregation laws until their numbers increased by 1910 due to the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) pushing people out of México and the need for agricultural labor pulled Mexicans to the U.S.

Since many ethnic Mexican families migrated to new jobs every two to three months following the crops, their children’s school attendance could be sporadic. At that time, schools were divided between elementary (K-8) and high school (9-12). Since few employment opportunities existed outside of agriculture before WWII Mexican children were encouraged to work in order to supplement the family income or drop out of school after the 8th grade. After WWII, educational opportunities changed for ethnic Mexicans. Young people began attending high school and college, and skilled, higher paying jobs opened up to them. In post-war California, attitudes toward ethnic Mexicans slowly changed. Ethnic Mexican soldiers had become “brothers in arms” during the war as they fought in Anglo units, not segregated as African American soldiers had been. (See Civil Rights section for court cases and the ending of California school segregation.)

Title: Mayfair School Class Portrait with Christmas Tree, c. 1940

Date: 1935-1950

Collection: History San José Online Catalog

Owning Institution: History San José Research Library

Source: Calisphere

Permalink: https://calisphere.org/item/ac5699114d7befb729677d8c6cae3988/

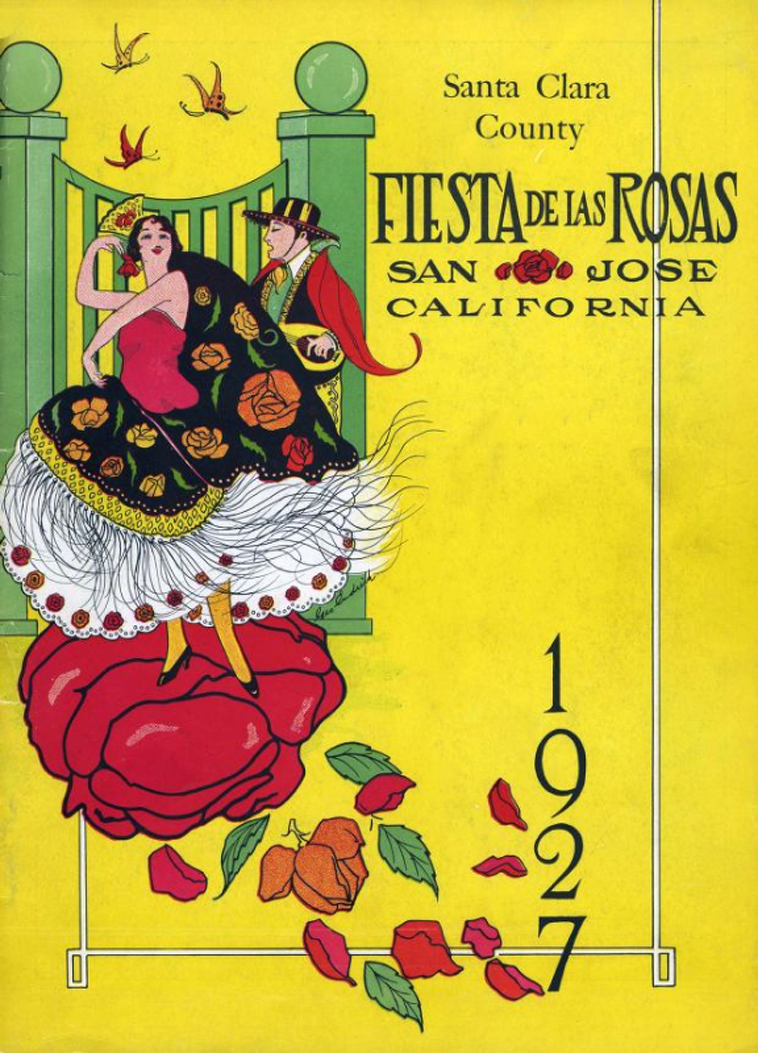

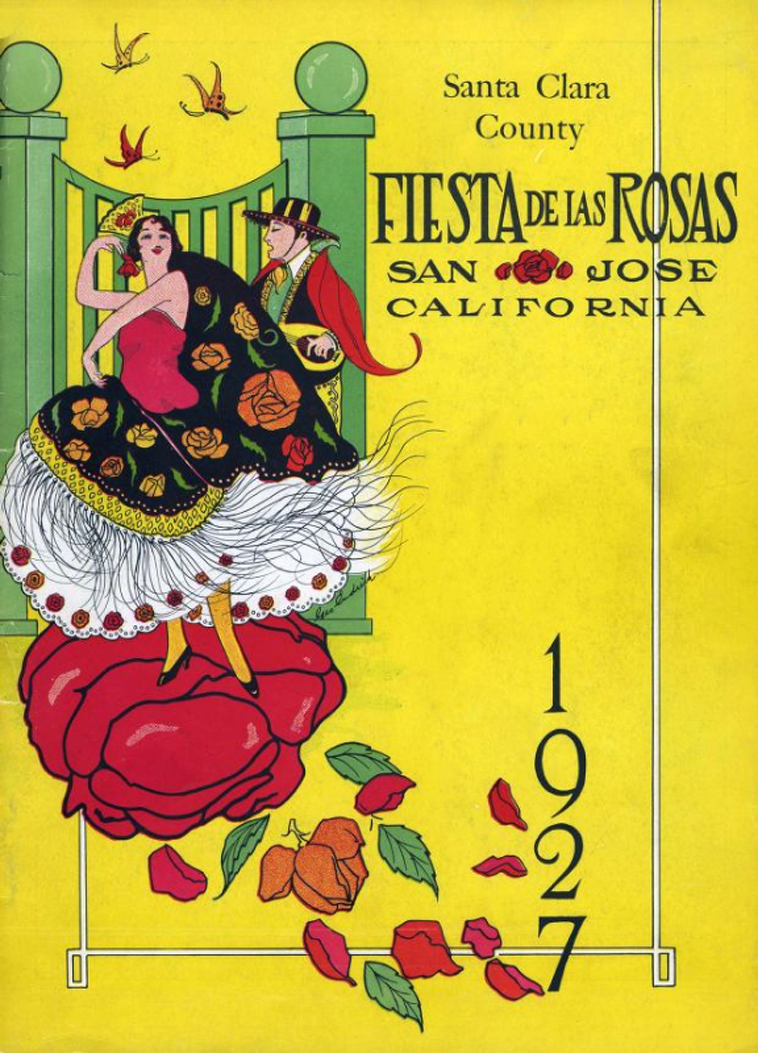

Mythologizing the Past While Discriminating in the Present

Ironically, in the 1920s and 1930s, at a time when Mexicans were being pushed to the economic and geographic periphery of San José, Anglo city boosters promoted a parade, Fiesta de las Rosas, celebrating the region’s so-called Spanish (European) or “civilized” history. The event started as The Rose Carnival in 1896 and became the Fiesta de las Rosas in 1926 and lasted until 1933.

In this instance, as historian Stephen Pitti notes, Anglo citizens connected their shared European white heritage with an imaginary Spanish-European California, an explicitly non-Mexican past. A few of the region’s remaining Californios were considered worthy of celebration, such as Santa Clara’s Encarnación Pinedo. Historian/journalist Carey McWilliams observed that the Anglo population considered these particular Californios to be the living embodiment of the “Spanish fantasy heritage.”

During the 1910s and 1920s, fiesta parades took place throughout California and were wildly popular, particularly in Los Angeles and Santa Barbara; some continue on today. Celebrations and theatrical performances using the themes of California’s mythical past were held throughout California in plays like “The Mission,'' by John S. McGroarty.

Santa Clara County hosted its first performance of “The Mission'' in 1915 at Santa Clara University. As PItti states, concerns over racial miscegenation and inter-racial romance were followed by two Fiesta plays that celebrated European White (Spanish or English) conquest over Mestizos and Indians, “La Rosa del Rancho, a Love Story of Early San José” (1927) and “The Madonna of Monterey” (1930). Anglos and ethnic whites played all the Spanish roles. For the audience, these celebrations affirmed the dominance of white European culture over the darker skinned Mexican “peons,” who were securely marginalized.

TItle: 1927 Souvenir of the Santa Clara County Second Annual Fiesta de las Rosas

Date: 1927-05

Collection: Fiesta de las Rosas Collection

Owning Institution: San José Public Library, California Room

Source: Calisphere

Permalink: https://calisphere.org/item/efc8cd7b4b1b14869244f43bc824d234/

Mexican Mutualistas, Home Clubs and La Comisión Honorifica in Santa Clara County

In Santa Clara County, immigrants formed associations with others from their original home in México or other regions of the Southwest. In San José, historian Stephen Pitti describes the rise of “town clubs” as the fraternal twin of the Mexican American mutualistas, or mutual aid societies. One important difference was that both men and women joined the town clubs while mutualistas were for men only. In the late 1920s, town clubs and mutualistas both helped with life insurance and funeral expenses for those without funds, fostering “a sense of local identity” while maintaining cultural and nationalist connections to México.

Town clubs linked transplanted Mexican residents from similar hometowns that were now living in Santa Clara County. These community organizations assisted families, developed community and promoted cultural events. They held social activities in local parks and residences to raise money to aid members and celebrate cultural ties, such as Fiestas Patrias. Most importantly, they advised newcomers in their native language on local laws, customs, and practices to help them integrate into American society. While Americanization programs were designed to replace immigrants’ native tongue and cultural traditions, town clubs and mutualistas aided immigrants in their transition to the new country.

Mutualistas and town clubs strengthened links to the Mexican consulate and to México as well. Using these connections, the consulate encouraged repatriation to México for San José immigrants struggling in the U.S. during the Great Depression. The Mexican consulate in San Francisco worked with the mutualistas to promote Mexican national celebrations of the Fiestas Patrias and to aid Mexican citizens.

During the Great Depression, the town clubs grew because it was impossible to afford annual visits to México as had been common in the 1920s. The California deportation campaign against ethnic Mexicans between 1929-1934 reinforced Northern California Mexicans’ reliance on their town clubs.

Prior to WWII and after, non-citizens were usually ineligible for social services. Mutualistas played an important role in redressing these inequities, advocating for their members with police and immigration authorities and granting small loans, as well as sponsoring local sporting events and cultural celebrations. The Mexican Consulate established the Comisión Honorifica Mexicana, an organization to promote cultural connections and aid Mexican citizens in the United States. The Comisión admitted all men of Mexican descent, regardless of citizenship.

Title: Court of Fiestas Patrias, Trinidad de la Grande on the right

Date: 1940s

Collection: Before Silicon Valley Project Archive, Trinidad de La Grande Martinez Collection

Owning Institution: SJSU Special Collections

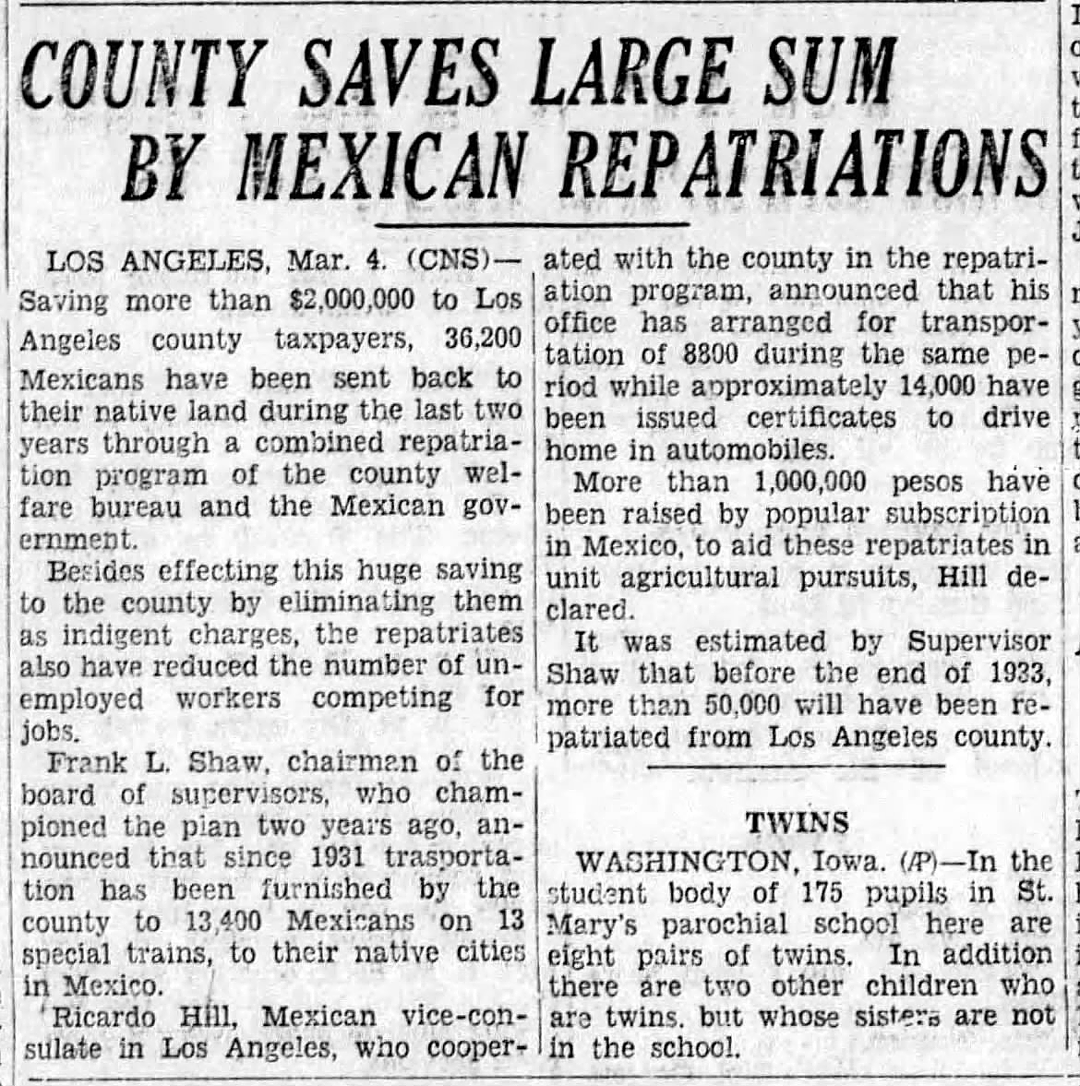

The 1930s Deportation/Repatriation Campaign in San José

In Santa Clara County, Mexicans did not endure the same threats from the Klu Klux Klan that their compatriots in Southern California experienced in the 1920s. However, with the 1924 Immigration Act, pressure was put on the U.S. federal government to establish the first Mexican border patrol.

In Southern California, the Mexican Deportation Campaigns from 1929-1934 further limited immigration. Santa Clara County, however, did not conduct extensive deportation campaigns, although Anglo trade unions tried to do so during the Great Depression. Instead, the Mexican consulate promoted the idea of repatriation to México to help those Mexican nationals who were suffering from the economic fallout from the Depression. As non-citizens, this population was ineligible for state or federal aid. During the 1930s, according to History Unfolded, 400,000-1 million of the nearly two million Mexicans living in the U.S., including American citizens, were either deported or repatriated to México. In San José, one third of the 4,000 Mexican residents chose to return to México in the Mexican government sponsored repatriation campaign.

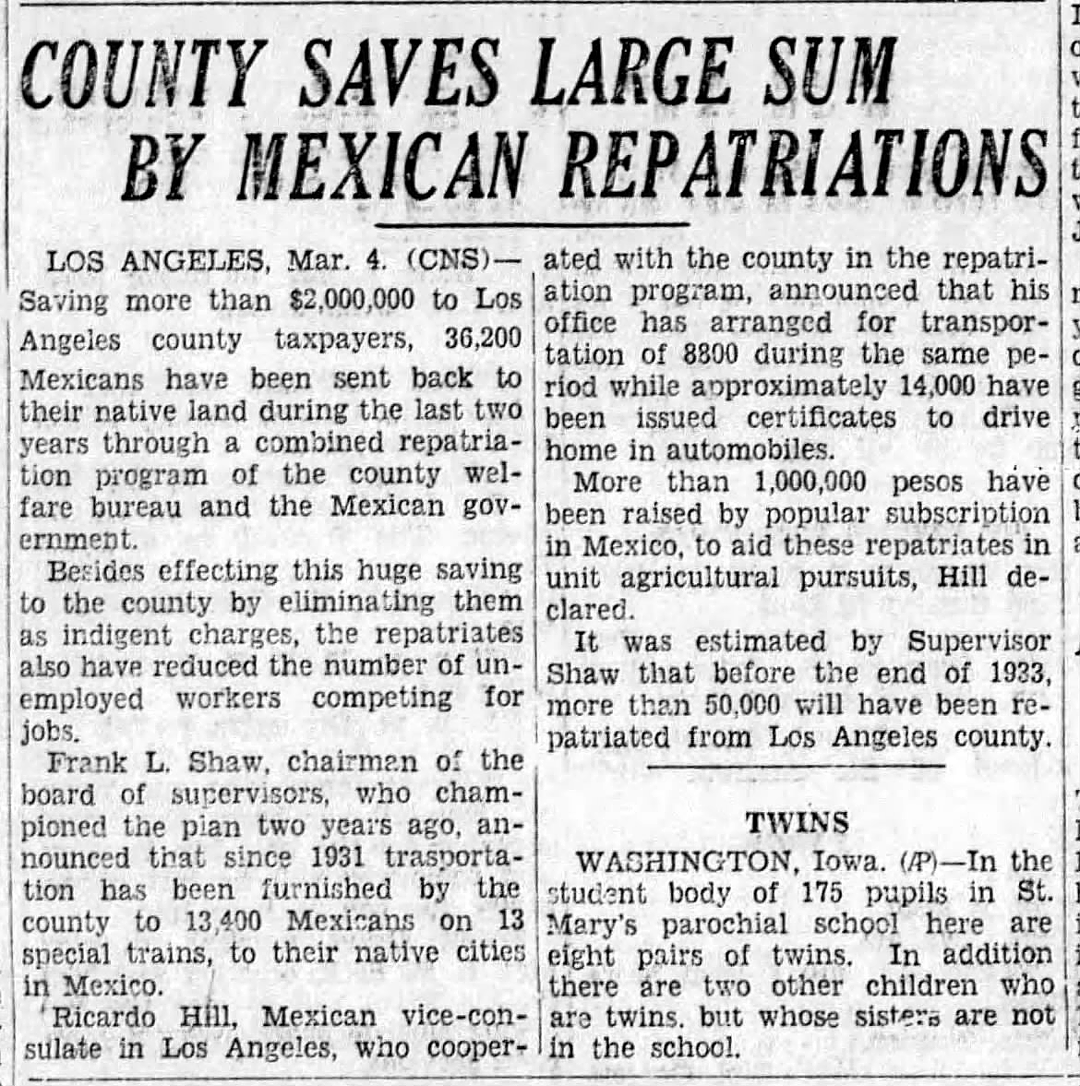

Title: Article on Repatriation

Date: 04 March 1933, Sat. p. 4

Collection: Monrovia News-Post, Monrovia, CA

Source: https://www.newspapers.com/clip/69883035/monrovia-news-post/

Mexican Businesses in Downtown San José, WWII to 1960

Historically, American settlement was concentrated east of the old Pueblo, with new businesses on 1st, 2nd and 3rd Streets. The ethnic Mexican residents of Santa Clara County considered Market Street the line between the American area and the Mexican Downtown Colonia. Restrictive housing policies had created segregated neighborhoods, and it was commonly understood that public accommodations were racially restricted until the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Stores, restaurants, bars, and shops that served Mexican customers were located on Market Street or the portions of 1st, 2nd, or 3rd Streets south of Santa Clara Street. On weekends, Mexican workers from across the County congregated to do their weekly shopping, see a movie, or get a haircut. By 1960, Mexican Americans and Mexican nationals comprised one-fourth of Santa Clara County’s population and were a major factor in the regional economy. Urban redevelopment and freeway construction would displace a large number of residents of the Downtown Colonia, contributing to the closure of many Mexican businesses in the area.

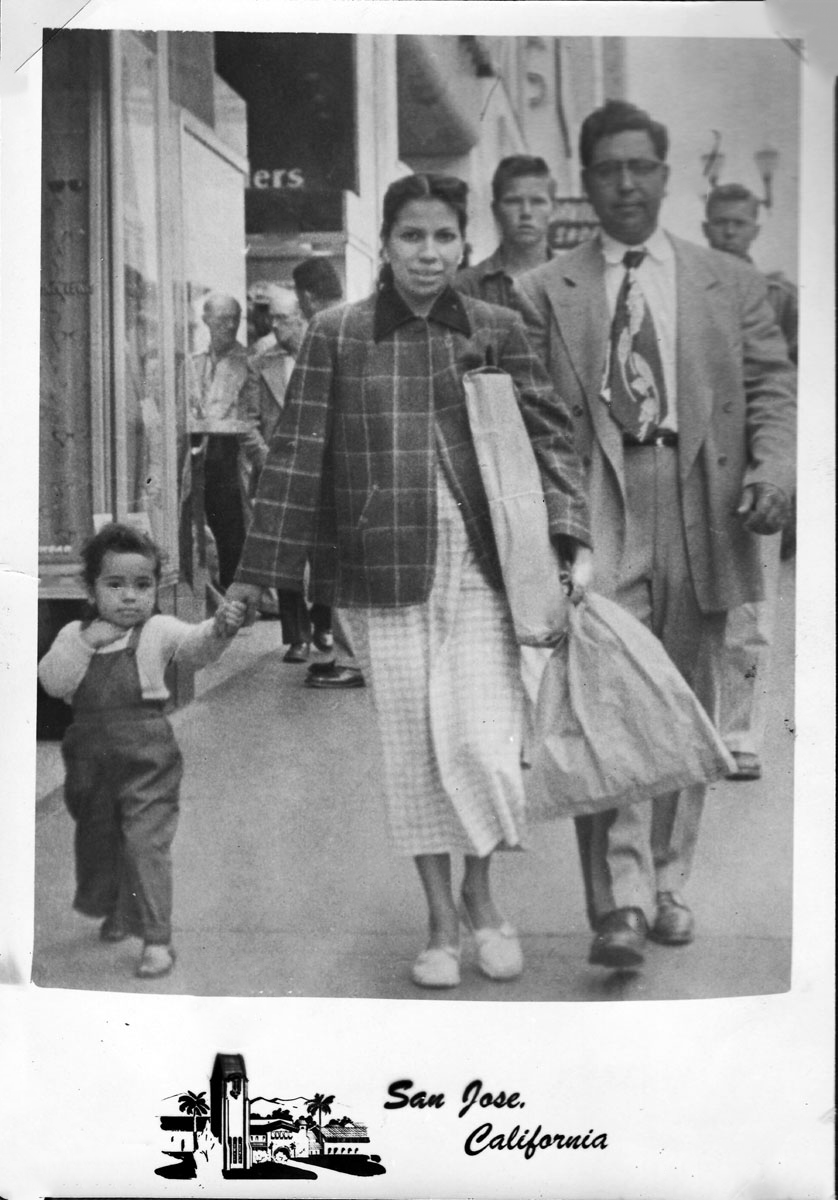

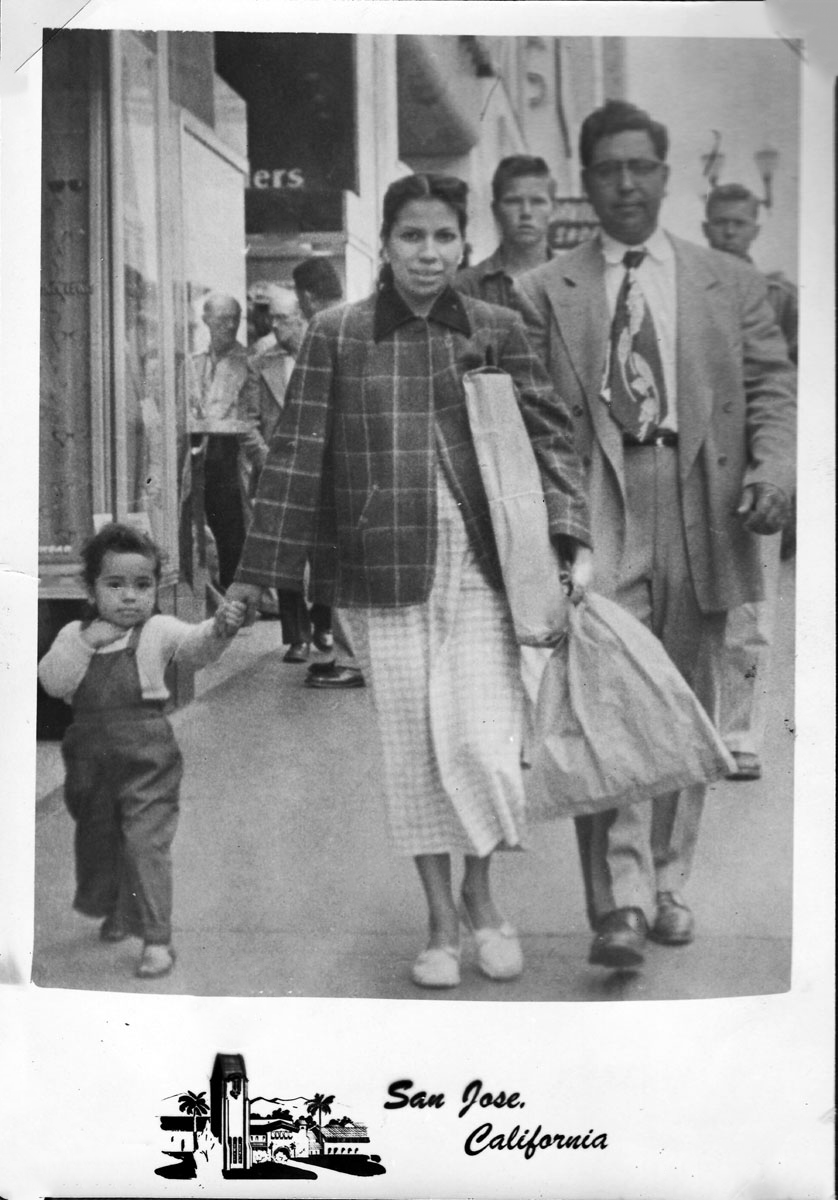

Title: Pantoja Family in Downtown San José

Date: 1955

Collection: Before Silicon Valley Project Archive, José Pantoja Family Collection

Owning Institution: SJSU Special Collections

Mexican Entertainment in Downtown San José, WWII-1960

Downtown San José was the regional social hub for Mexican residents. On weekends, locals were joined by farm workers from nearby rural regions of the San Joaquin Valley to eat at a Mexican restaurant, watch a Spanish-language movie, meet friends for a drink, or go dancing.

On Market Street a strip of restaurants and stores catered to a Mexican clientele. After WWII, the Liberty Theater, the Victory, the Lyric, and the José offered first-run movies from México and staged personal appearances from singers and performers. Local ballrooms (see ballroom section) also enlivened the downtown social scene. The proximity of nightclubs, many Mexican restaurants and shops that encouraged their patronage, was a major draw to those who had only limited services in their small communities or the work camps scattered throughout the region.

After WWII El Eccentrico, the local Spanish-language entertainment magazine, established in 1948 (running until 1980), carried ads for shops, grocers, restaurants, and real estate and insurance agents catering to a Mexican clientele. Alongside the ads were announcements of clubs, concerts, and community events.

Title: “El Eccentríco” Cover

Date: Dec. 1950, Vol. 1, No. 10

Collection: “El Eccentrico” Collection

Owning Institution: California Room, San Jose Public Library

Source: Calisphere

The Influence of Mexican Music on San José, WWII to 1960

In 1942, the U.S. government instituted the Emergency Farm Labor Program, known as The Bracero Program, bringing in a new group of immigrants from the border regions along with a new style of music called Norteño or Tejano. The musical traditions of the Tejanos of South Texas and Norteños of Northern Mexico have been influenced not only by the mother country, México, but also by their Anglo American, African American, and immigrant neighbors like the Czechs, Bohemians, and Moravians as well as the Germans and Italians. From these influences came the polkas and accordion music that are so closely associated with this style.

Many of these Mexican immigrants were from rural areas, and more familiar with the Mexican orquesta tipica, or string band, and regional music from their homelands, such as the conjunto. The conjunto mixed the folksy storytelling corrido, the dance form huapangos, and the traditional ranchera with European instruments such as the accordion. In the borderlands of the American Southwest, the orquesta Tejana was patterned after the big bands of this period and appealed to an acculturated Mexican American audience. A fusion of these styles with mariachi and rock-n-roll in the late 1950s would result in a new style referred to as Tejano or Tex-Mex.

Mexican corridos, a popular music genre of the late 1920s to the mid 1940s, provided a way for ethnic Mexicans to document their immigration, migration, work and day-to-day living experiences. Frontera music curator Juan Antonio Cuellar notes that corridos were a form of oral history documentation adapted to music. News headlines became corridos stories. Cuellar describes corridos as “the newspapers of the Mexican working class”.

During the 1920s, Latin American music and performers became popular among elites of all continents, who often preferred simplified romantic ballads and Latinized American pop music. Both this “society rumba” and Afro-Cuban influenced Latin American music such as mambos, were popular with local Latino audiences for the next several decades. Out of the big band era arising in the mid 1930s through the 1940s, Mexican musicians added a Mexican twist and created Pachuco Boogie.

The largest events in San José were often held at the Municipal Auditorium, with performers such as Tito Puente, Desi Arnaz, and Lalo Guerrero playing for dances. Other ballrooms included The Balconades and The Palomar/Starlight ballrooms. During the war years, big bands–such as Benny Goodman, Glen Miller, Xavier Cugat, Jimmy Dorsey, and Artie Shaw–all featured Latin songs. In the early 1950s, American bands playing the Latin rumba, including nightclub performers such as Xavier Cugat, Desi Arnaz, and Carmen Miranda, were often featured in movies and television.

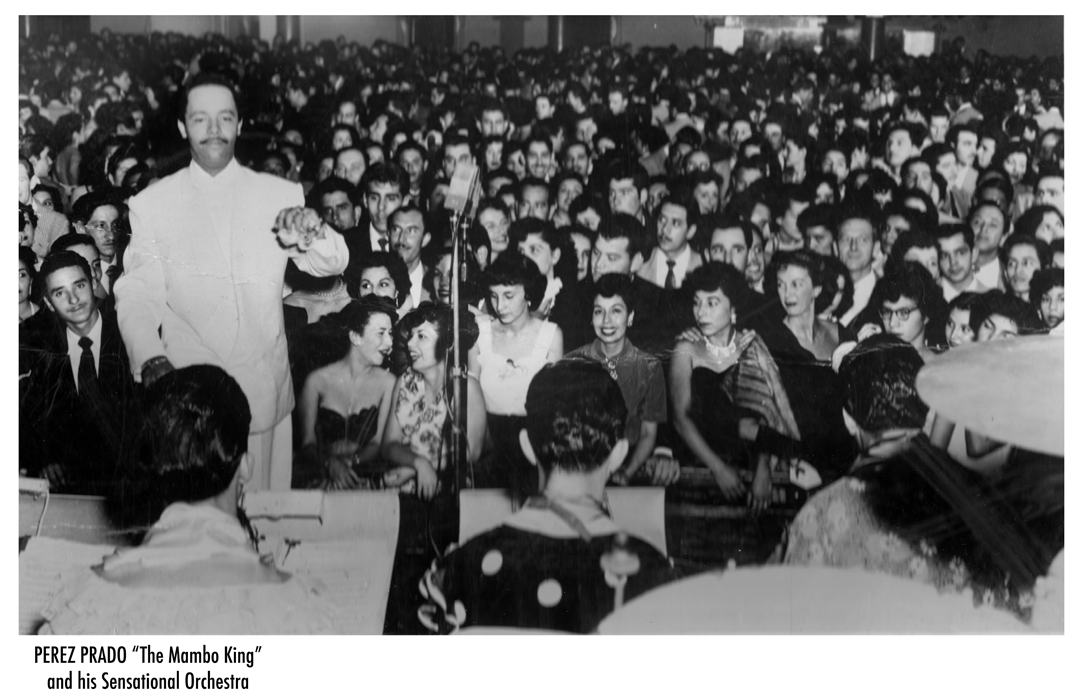

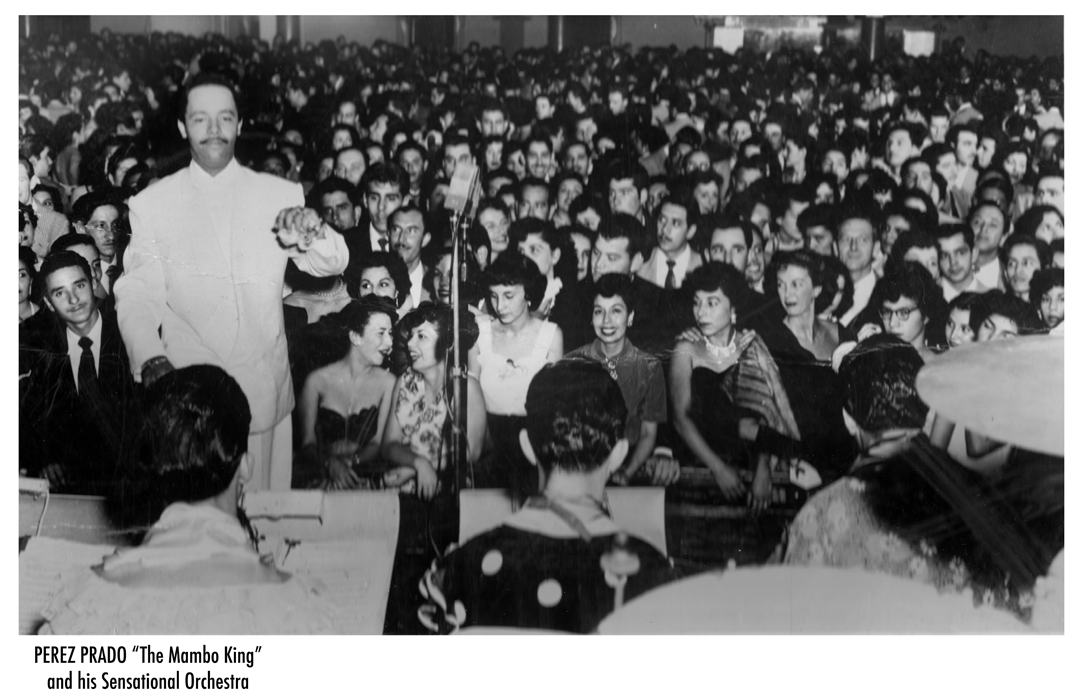

Title: Pérez Prado Band

Date: circa 1950

Collection: Before Silicon Valley Project Archive, Clay Shanrock Family Collection

Owning Institution: SJSU Special Collections

San José Sabor: Local Mexican Musicians, Singers, Bands and Radio Stations in San José, WWII to 1960

San José gave rise to several nationally recognized musicians and singers, such as the Montoya Sisters from the Eastside. From the 1940s through the 1960s, Agustin De La Grande was an important performer who, through his Academia de Musica, mentored many aspiring local musicians and young people in his marching band and orchestra. Agustin taught his daughter Trinidad De La Grande Martínez as well. She learned to play several instruments and filled in positions in her father’s band when needed. Some of De La Grande’s students went on to form their own groups, like the Bernie Fuentes Band, the house band at the Palomar. Low pay for performances forced many musicians to work during the day, many in the canneries, and perform in the evenings after work. This was the experience of musician Coronado Barrientes, drummer Rudy Coronado, and singer Francis Pacheco Wells.

By the 1950s, young Mexican Americans, like their peers, were attracted to the new musical styles of rhythm and blues and rock-n-roll. During this time, radio was becoming the prime source of Spanish-language entertainment and information for the expanding Mexican colonias. Many ethnic Mexicans could not afford to buy records or attend concerts, but they loved listening to music in public spaces that had jukeboxes or on the radio. Several local radio stations developed Spanish programs, some of which were broadcast by Jesus Reyes Valenzuela, born in Shafter, Texas, and the first Spanish language broadcaster to operate in Santa Clara County. In the late 1940, his "Hora Artistica" was aired on KSJO Monday through Saturday. Mornings and afternoons featured the beloved singers of Mexican rancheros--Pedro Infante, Jorge Negrete, Luis Pérez Meza, Luis Aguilar, and Lola Beltran. Radio Station KAZA in Gilroy started in the 1950s or 1960s. It was Portuguese owned and had 80% Spanish language programming, 7% Portuguese language programming and the remainder was English programming. In the 1960s, radio stations began to feature live remote broadcasts from community events featuring local singers and musicians.

Title: Exhibit De La Grande Colln_Agustin De La Grande Directing_other performers.tif

Collection: Before Silicon Valley Project Archive, De La Grande Collection

Owning Institution: SJSU Special Collections

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

Mexican Dancehalls, Lounges and Ballrooms

Public dance halls in the U.S. first appeared in urban areas around 1845, often as dance halls associated with the working classes, selling liquor or operating as saloons. In polite society, public dances were charity events, club or lodge dances, and held at dance palaces or pavilions associated with amusement parks. Providing a new social setting where people could make new acquaintances and socialize with those of diverse backgrounds, while observing the latest trends and fashions, ballroom dancing altered social patterns between the sexes, different social classes, and different racial and ethnic groups at the turn of the 20th century.

With the growth of popular music and dancing came new neighborhood dance halls or private clubs. Public dance halls and pavilions, often offering dancing lessons, did not appear in local city directories until 1927. From 1927 to 1945, four main ballrooms were located in downtown San José: The Balconades on Santa Clara Street, The Rainbow Ballroom on San Antonio Street, The Majestic on Third Street, and The Palomar Gardens on Notre Dame Street. These offered music by varied racial/ethnic bands in front of an integrated audience, although a majority came from the same racial/ethnic group as the band playing. In 1946, two other local venues were added: The Italia Hall, operated by Prospero G. López, and The Townsend Hall, owned by Frank and Angelo Boitano. These informal settings often catered to the non-Anglo working class and ethnic communities who could not afford, and often were not welcome, in the major ballrooms. In the late 1950s, John Zamora, a local Mexican businessman who had grown up as a farmworker and then went on to college, opened several restaurants with lounges where his musician brother Bobby Zamora and his band performed.

Music producers, such as Frank Davila, understood that the availability of both radios and record players to a wider audience helped to popularize new artists and sell records. While lounges and nightclubs offered an audience of 300-500 each night, large ballrooms might attract 3000-5000 potential record buyers. These large venues were ideal for aspiring performers and big-name attractions with new albums. During the 1930s, large public dances and concerts were held at The San José Municipal Auditorium, offering traditional Mexican and “Spanish-American” music. According to public historian Suzanne Guerra, who did an historical context on the last surviving ballroom from the Big Band Era, The Palomar, constructed in 1946, was the only venue where an integrated audience could attend social dances and musical concerts in an elegant setting.

San José provided numerous performing venues. Although not as large a market as Los Angeles, the proximity to the Bay Area and the many small venues in Santa Clara County enabled musicians to supplement jobs in the canneries with weekend performances at dance halls and clubs. This was the experience of Francis Pacheco Wells, vocalist for Dan's Combo, performing on the weekends at Maria'a Cocktail Lounge (728 N. 13th St. San José). Family celebrations and community fundraising events were often held at ballrooms and public halls. Musical parties like the multigenerational tardeada reinforced family and community ties, with both traditional musical styles and contemporary music, food and entertainment for largely Spanish-speaking audiences. In this way, the mix of musical styles in San José was continually renewed with each wave of immigrants and their distinct musical traditions.

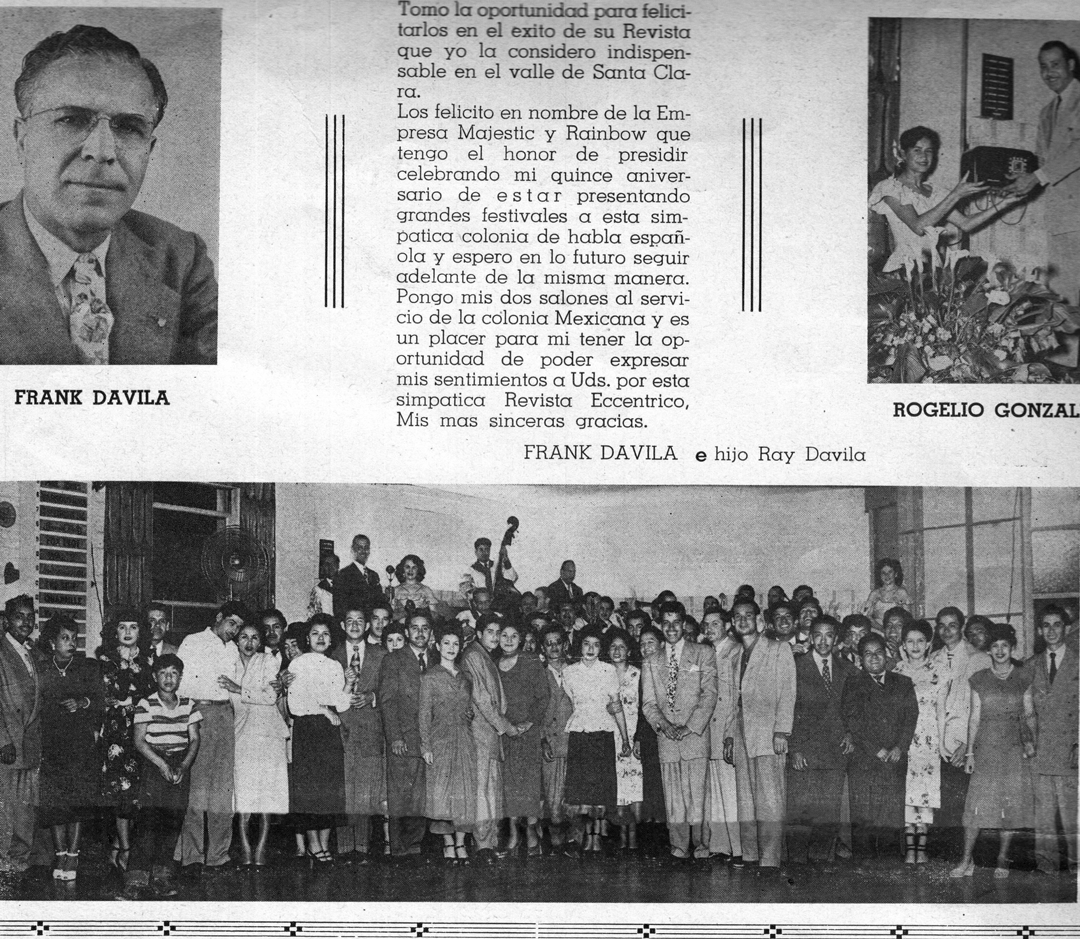

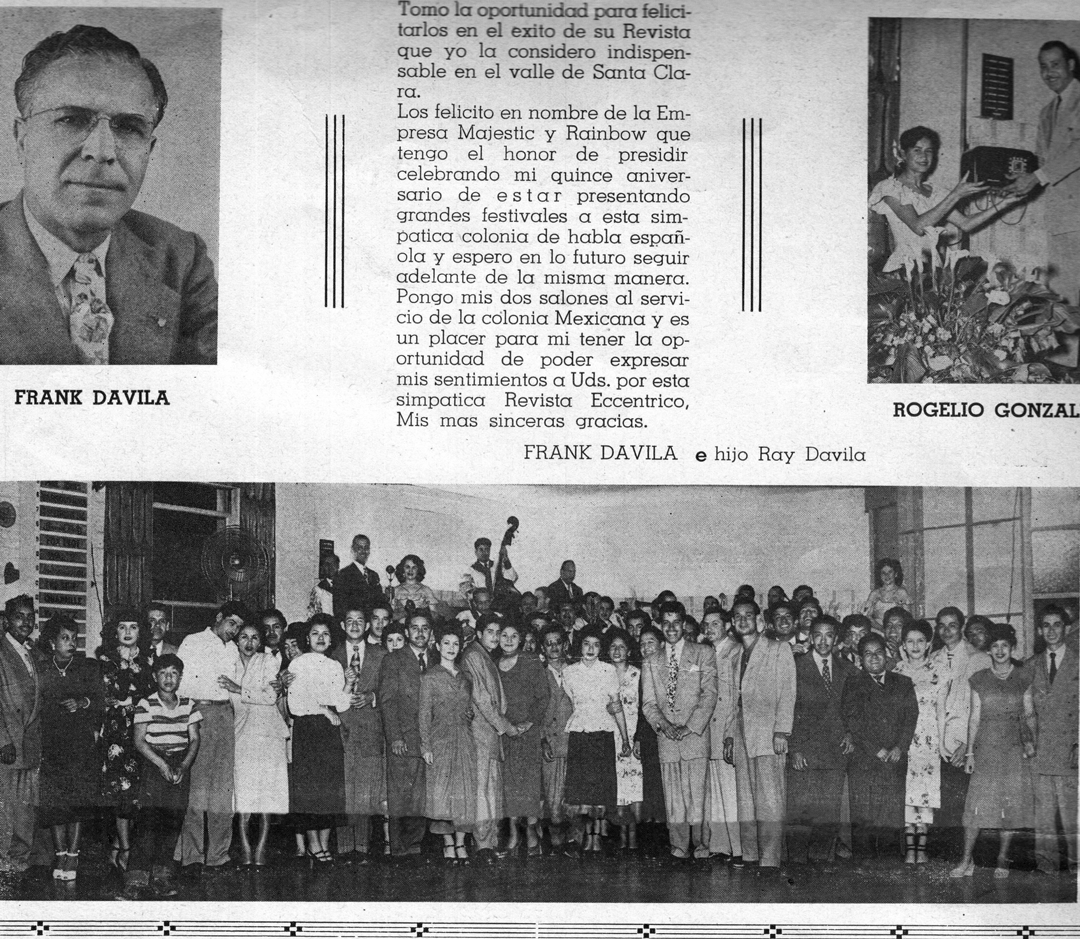

Title: EL Eccentríco

Date: August 1949

Collection: EL Eccentríco Collection

Owning Institution: California Room, San José Public Library

Source: Calisphere

San Jose’s Zoot Suit Riots

The Zoot Suit Riots in 1943 were a series of violent clashes in Los Angeles between U.S. servicemen, off-duty police officers, and civilians who confronted young Latinos and other minorities. The riots took their name from the baggy zoot suits that accentuated their movements worn by many young men in the 1930s in dance halls in the East. The zoot suit became a popular trend among young men in African American, Mexican American, and other minority communities in California. Anglo Americans knew very little about the Mexican American community, who were generally portrayed by local police and newspapers as problematic lawbreakers, drunks, or criminals. Young Mexican Americans were portrayed as pachucos (juvenile delinquents) or gang members who posed a danger to society.

Conflicts between police and Mexican youths spread from L.A. to the Bay Area during the summer of 1943. In San José police carried out a similar harassment of Mexicans in the name of “keeping the peace.” In one instance, “intent on starting their own ‘zoot suit’ war,” a group of sailors hunted down Mexican youths as they spilled out of the downtown dance halls and ballrooms on Market Street in the late hours of the night. Local Judge William James stated, that "we certainly don’t want to see anything happen here like it is in Los Angeles,” handing down probation if the arrestee would join the military.

Large groups of assembled Mexican young men were often considered suspect. One night, two San José police officers tried to arrest two Mexicans having a fist fight in St. James Park. The two escaped but were caught in front of a dance hall where a group of Mexican cannery workers and zoot suiters were just leaving. The group attacked others, who followed the officers and the youths back to the police station. When the youths fell and appeared injured, a large group of military and local police arrived to disperse the crowd.

At a local Santa Cruz beach, Marines drove visiting Mexicans away. Five Mexican young men were held in the San José Jail “because of their large size.” In 1944, 25 zoot suitors were arrested for “frequenting streets and public places in the late night,” and three of what the San José police considered “bad boys” were deported to México. That same year, Gilroy police arrested thirty Mexican youth “for violating curfew laws.” Toward the end of the War, another clash occurred between zoot suiters and sailors in St. James Park, the same location as the lynching of Tiburcio Vásquez in the late 1800s, ending with the arrest of the Mexican youths and release of the sailors.

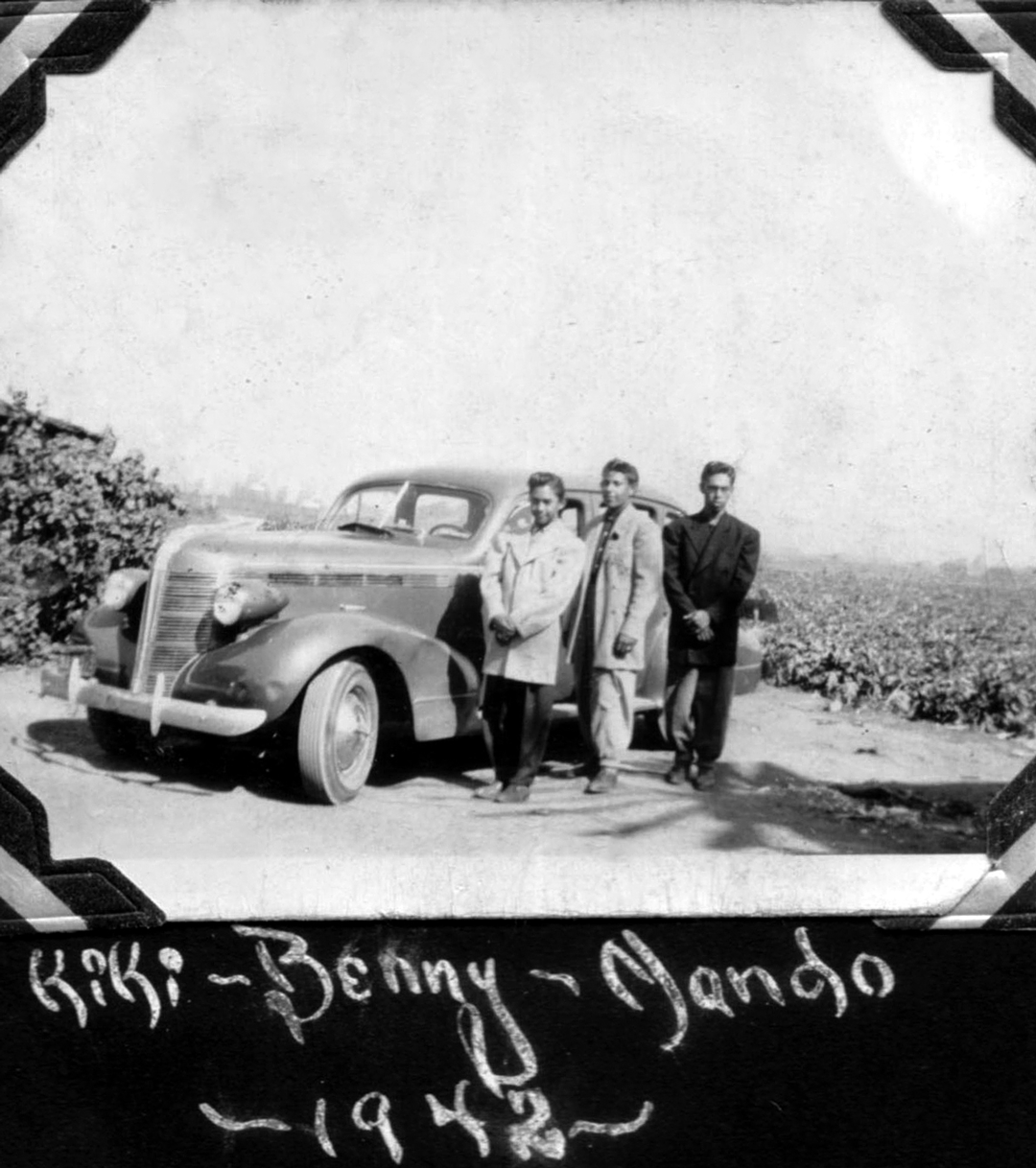

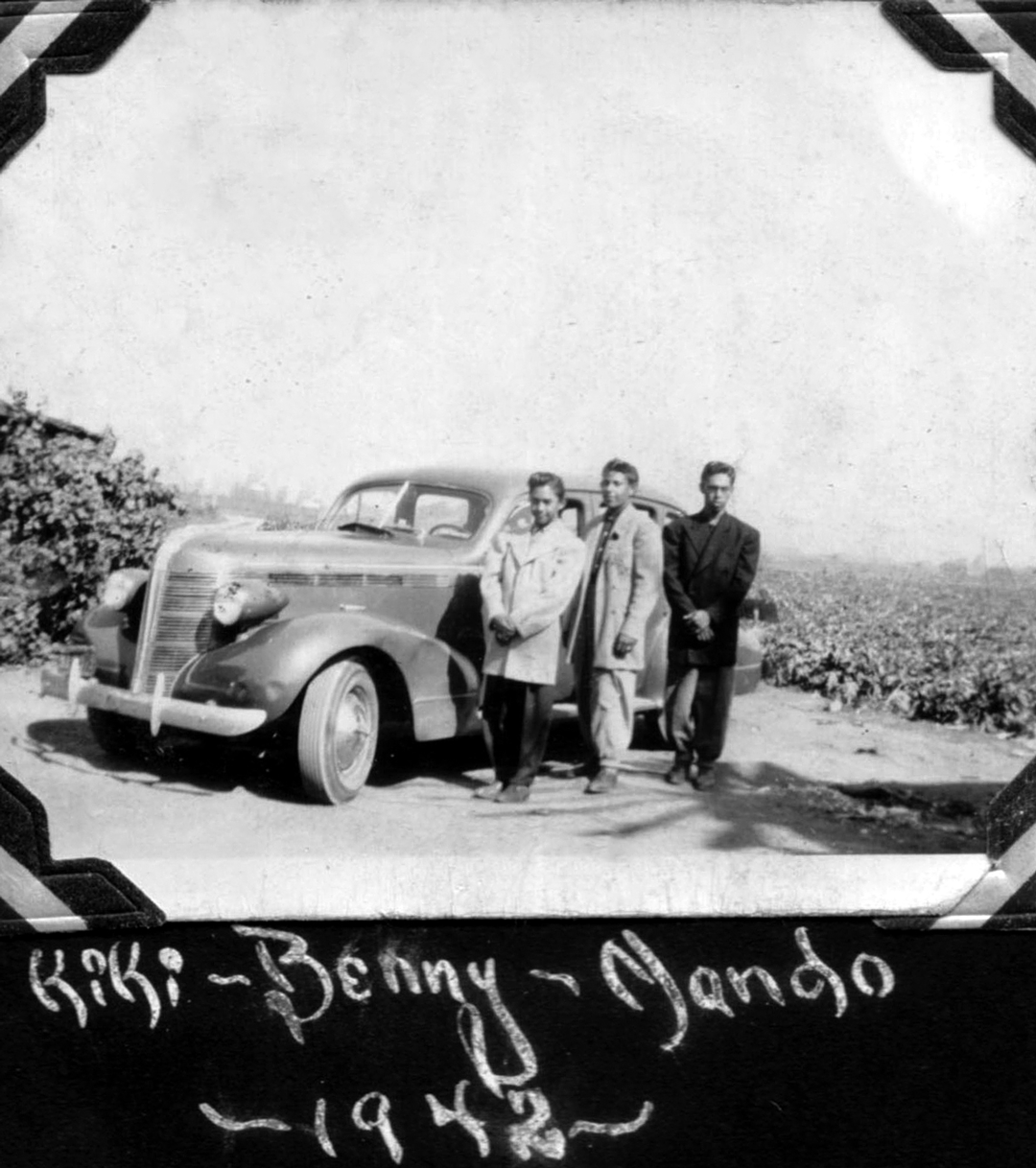

Title: Kiki, Benny, Nando 1942

Date: 1942

Collection: Before Silicon Valley Project Archive, The Fernando Chávez Family Collection

Owning Source: SJSU Special Collections

Rock and Roll Riot of 1956

Few people have heard about what became known as the first Rock ‘n’ Roll Riot at The Palomar Ballroom on the night of July 7, 1956. Opened in 1947, the Palomar was the first integrated ballroom in San José, where big bands, vocalists, and jazz artists from across the country, México, Latin America, and the Caribbean performed in front of an integrated audience.

In 1956, Rock 'n' Roll was still new, and the big attraction that night was the now legendary Fats Domino, who arrived very late to a large crowd inside the ballroom and hundreds waiting outside. By the time the band started, some patrons were already drunk and unruly. During the intermission, beer bottles were thrown; then a brawl began as lights were smashed, chairs and tables destroyed, and many were injured. Nearly a dozen people were arrested.

Accounts of the brawl appeared in every major newspaper in the country, and the San Francisco Chronicle termed the affair a “Rock ‘n’ Roll Riot,” linking the music with the breakdown of public order. One week later the San José City Council considered a resolution to ban rock and roll at city-owned venues, eventually establishing a new ordinance requiring all drinks at concerts to be dispensed in paper cups. Just as the zoot suit had been used to criminalize youth of color in the 1940s, Rock ‘n’ Roll music was used to vilify another generation of ethnic young people.

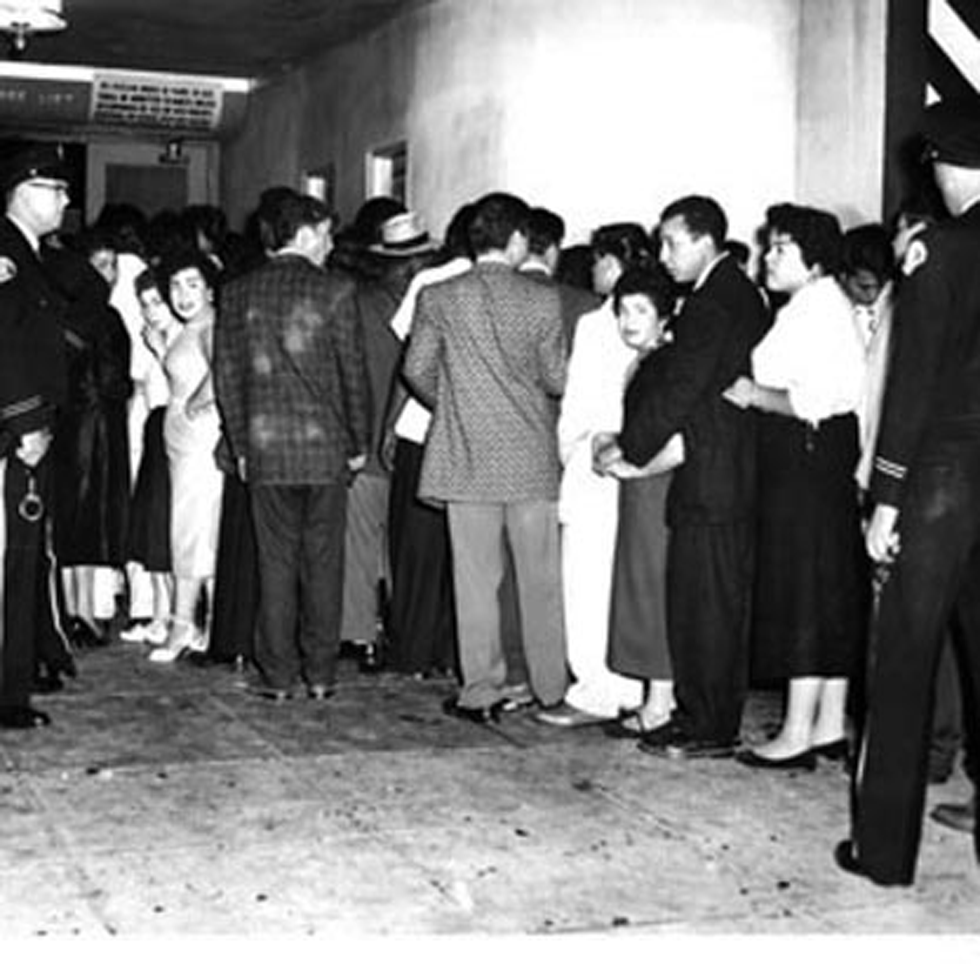

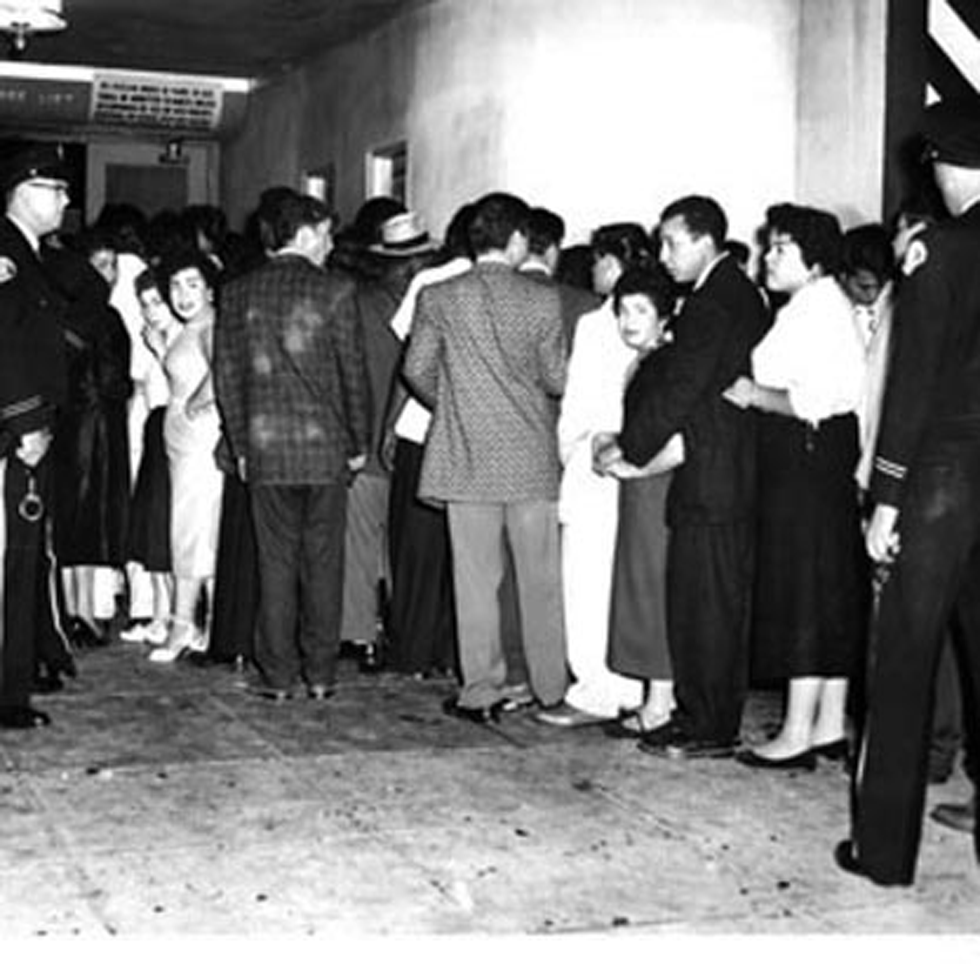

Title: Palomar Ticket Line

Source: San Jose MercuryNews

Public Domain

Leisure Time with Social and Car Clubs

With non-agricultural jobs increasingly becoming available to ethnic Mexicans after WWII, more Mexican American youth began to attend high school and college. In the 1950s, a proliferation of social clubs, like Club Cuauhtémoc, provided a place for young ethnic Mexican urban professionals to gather. Some social clubs functioned similarly to town clubs, like The Del Rio Club, bringing together people from the same town or region. Some social clubs focused on public service, holding fundraisers for charitable causes or organizing around community issues such as voter registration and Latino candidates. Social clubs sponsored dances, such as the traditional formal Black and White Ball, organized outings such as picnics, or group activities, including bowling teams.

In the 1950s and later, lowriders in San José were mostly Latino, converting older cars for cruising, car shows, and design competition at events, adorning their cars with Mexican American imagery and vibrant colors. As small groups organized into regional clubs, lowriding became a multigenerational cultural activity, with the embellished car club jacket created to identify the local group. These “jacket clubs” were popular in San José, though local police banned them from 1986 to 2022 on the basis of preventing gang violence and related crime. The intersection of Story and King in the Eastside is now recognized as the meeting ground for generations of Lowriders and San José as a center of Lowrider culture.

As the Mexican American community became more established, new organizations were formed, such as the Mexican American Chamber of Commerce and the Mexican Masonic Lodge. The number of social clubs, ethnic organizations and fraternal associations increased among the post-WWII growing Mexican middle class and young professionals, who announced their activities regularly in the bilingual, regional entertainment magazine El Excentrico (FKA El Eccentríco). Church groups, clubs, and organizations were also involved in charitable activities and community projects.

Social clubs, sporting events, baseball and basketball clubs, and car clubs promoted ethnic consciousness, built solidarity, and sharpened organizing and leadership skills. They offered young Mexican Americans opportunities to compete on an equal basis outside the immigrant community. Such cultural activities generated networks, created bonds of solidarity, and provided a strong foundation for the Mexican civil rights movement to emerge within a flourishing community of musicians, artists, sportsmen, and club members.

Title: Bernie Fuentes Band, Club Cuauhtémoc Social Dance

Date: 1950s

Collection: Before Silicon Valley Project Archive, Brooks Family Collection

Owning Institution: SJSU Special Collections

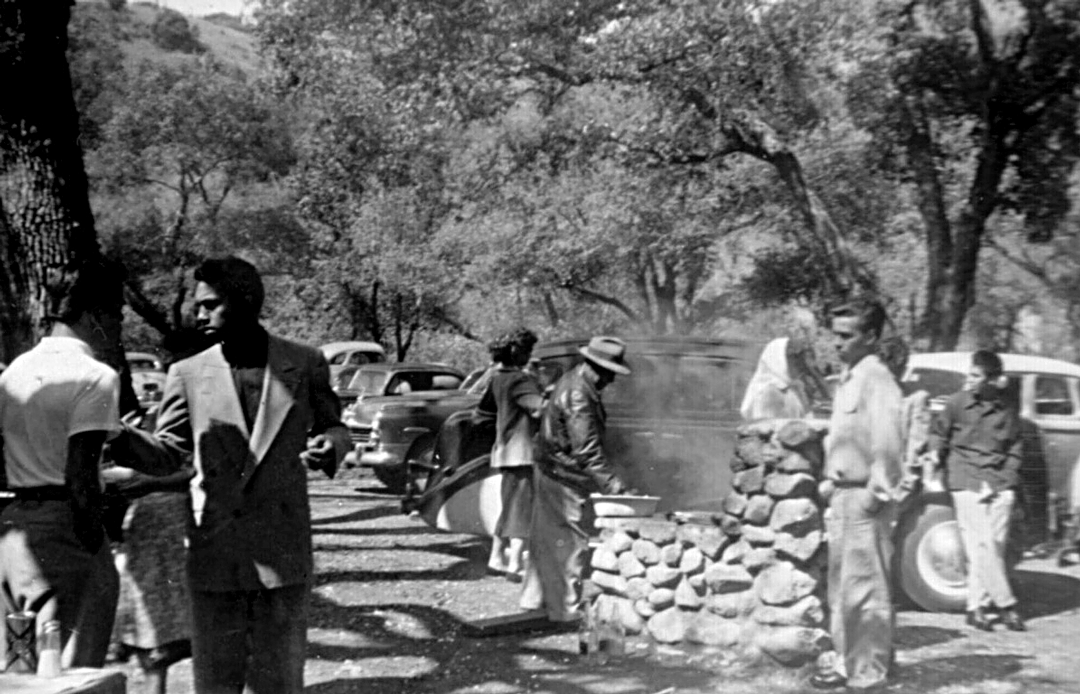

Recreation at Parks, Churches, Beaches, Mountains and Beyond

Local parks were popular sites for large family gatherings and youth activities. During the post-WWII period, there were few parks or recreation centers in Mexican neighborhoods. Families might host small groups at home but had to travel to parks like Alum Rock to host larger groups. With the lack of neighborhood parks, the Catholic church often filled the gap by providing a place for recreational activities and community events. Catholic churches became important public spaces, with social halls used for family or community events, art programs, English classes, and neighborhood meetings. Leaders in these Catholic churches often moved on into positions of influence in labor movements and political organizations.

While the majority of ethnic Mexicans in Santa Clara County identified as Catholics, there were also Mexican Baptists, as well as Presbyterians, Methodists, and various evangelical denominations. While Mexican cultural traditions were acknowledged, many churches sponsored youth baseball and basketball teams in order to engage immigrant families in American culture and recreation. Neighborhood schools also offered organized sports.

During the post-war years, automobiles became more affordable, and families began to travel longer distances to the beach and Boardwalk in Santa Cruz, to camp or hike in the redwoods or Mt. Hamilton, tour San Francisco, or even vacation in México.

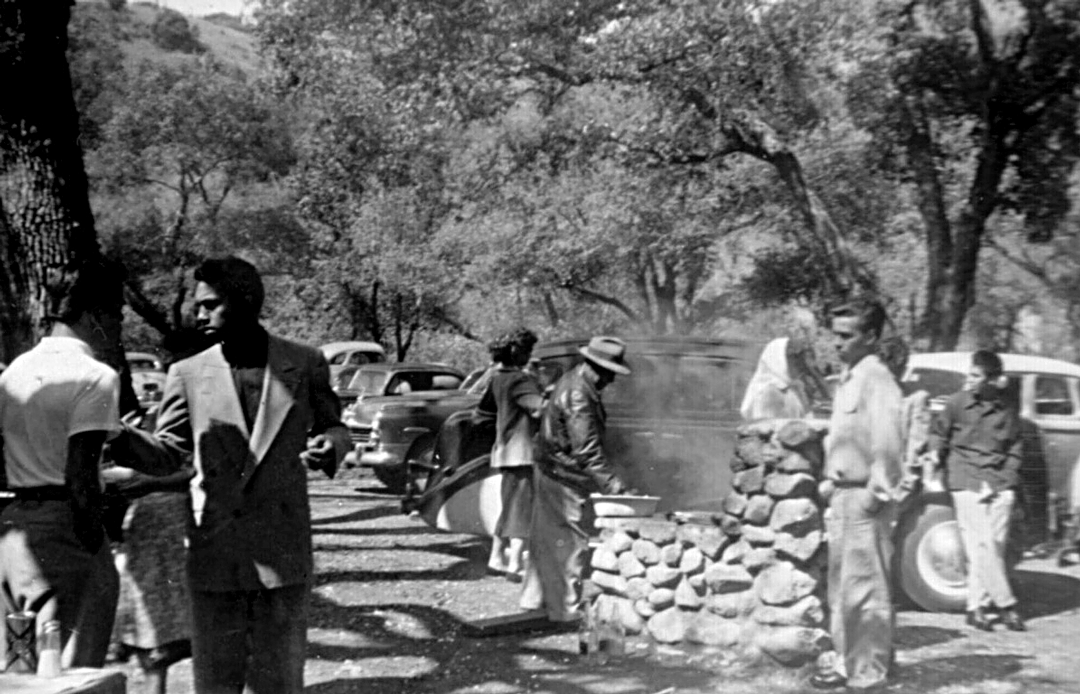

Title: Fernando Chavez and Friends at Alum Rock Park

Date: 1950s

Collection: Before Silicon Valley Project Archives, Fernando Chávez Family Collection

Owning Institution: SJSU Special Collections

The Mountain View Colonia, WWII-1960

The Hispanic roots of Mountain View stretch back to the Mexican land grant of Rancho Pastoria de Las Borregas of 8,800 acres that included lands in current Sunnyvale and Mountain View, granted to Francisco Estrada and his wife Inez in 1842. When the Estradas died in 1845 they left their land to Inez’s father, Mariano Castro. Castro sold the eastern half of the rancho, what is now Sunnyvale, to Irishman Martin Murphy, Jr. Murphy had arrived in 1844 and planted Santa Clara County’s first orchard on his newly acquired land. Castro died in 1856, leaving the Mountain View portion to his son, Crisanto Castro. Like other Mexican Californios, the Castros fought in the American courts from 1852 to 1871 to validate their land grants but lost most of it to squatters and lawyers fees. The Castro family remained in Mountain View until 1958, when they sold their remaining 23.5 acres to the City of Mountain View.

In the early 1900s Spanish immigrants arrived in Santa Clara County. Many who had worked in the orchards and canneries in the 1920s and 1930s moved to Mountain View, California, settling in the northern section of the city above the canneries, packinghouses and railroads. These included the Mountain View Fruit Packing Company, Clark Canning, and San José Fruit Preserving Company. Around 1920, the P.L. Sanguinetti Cannery in Mountain View was acquired by the Richmond-Chase Cannery, one of the largest in California.

Sharing a common language, the Spanish community welcomed Mexican immigrants who arrived in Mountain View during and after WWII. This would eventually transform the Spanish neighborhood into the Mountain View Mexican Colonia. In such a small town, Mexicans did not form a separate commercial district but melded cultural traditions and a shared language. St. Joseph Catholic Church became the heart of the Colonia, and during the late 1940s to 1950 Father Donald McDonnell encouraged the Mexican community to address their financial, economic, and social needs by creating Club Estrella as well as a community credit union. Club Estrella hosted annual church and community events for the entire Spanish speaking community. Increasing urbanization and highway expansion during the 1950s and 1960s brought major thoroughfares through the heart of the district and decimated the established Mountain View Colonia. Father McDonnell was assigned to the Mexican mission in Eastside San José in 1951, and helped establish the San José de Guadalupe Church and became a mentor to César Chávez.

Title/Caption: Father Donald McDonnell, Parish Priest in Mountain View 1947

Date: 1947

Collection: Nick Perry Family Collection

Owning Institution: Mountain View Historical Association

Source: Mountain View Public Library

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

The Gilroy Colonia, WWII-1960

During the Spanish colonial era, two land grants (Rancho Las Animas and Rancho San Ysidro) comprised what is now the region known as Gilroy. Additional land grants were issued during the Mexican era. The city of Gilroy was eventually named after a Scottish immigrant, John Cameron, who came to Monterey in 1814 and changed his name to Juan Bautista Gilroy after converting to Catholicism. He worked on Rancho San Ysidro, marrying the ranchero’s daughter Maria Clara Ortega, and became a naturalized Mexican citizen. Eventually he inherited a part of Rancho San Ysidro and raised cattle. During the American Period, Gilroy incorporated as a town (1868), and most of the Mexican rancho land passed into the hands of Anglo farmers and ranchers. In the late 1850s much of Rancho Los Animas (12,000 acres) was sold to Henry Miller, a famed cattleman in the Miller & Lux Company, which lobbied for the railroad to run through Gilroy in order to facilitate their cattle raising/butchering operations. The area boasted prune, cherry, and apricot orchards, with the producer exchange Sunsweet overseeing the drying of these crops for market. In the early 1960s, orchards were replaced by row crops of tomatoes, sugar beets, and garlic.

Prior to WWII, Mexican immigrants migrated to work in the orchards and fields, living temporarily on the ranches where they worked. Some Mexicans, such as the García family who migrated from Texas, began moving into Gilroy during WWII. They initially bought a large apartment complex, the Guadalupe Apartments, on Eigelberry and 7th Street, and then opened the Post Office Market on 6th Street and Monterey Road, which they sold and then established García (card) Club in 1952 on Monterey Road between 6th and 7th Street facing the railroad. The Mexican businesses of the García family were unique. Gilroy was a small town, so there was not a separate Mexican business district, and Mexican residents did not attend separate schools or theaters. Instead Wednesday was “Mexican Night” at the Anglo-owned Strand Theater, with headliners such as Cantinflas appearing on occasion.

It was not until WWII and later that Mexicans moved into higher paid, unionized cannery work. Though still seasonal, it was flexible enough to allow workers to move to other jobs when necessary. Employment at the Felice and Perrelli Cannery (1914-1997) enabled several generations of Mexican families to establish roots in town. The Gilroy Mexican Colonia appeared south of 7th Street, with some settling on the westside of Monterey Road and the majority living east of Monterey Road next to the canneries and railroad tracks.

Title: Enumeration District Maps for Santa Clara County, California

Date: 1930 - 1950

Source: The U.S. National Archives

Link https://catalog.archives.gov/

The San José Mexican Downtown Colonia Before and After WWII

As more seasonal Mexican immigrant workers arrived in the Valley, civic leaders worried that a year-round Mexican settlement would lower Anglo property values. Between 1920 and 1945, racially/ethnically restrictive covenants (land deed restrictions) and racial/ethnic redlining (lender refusal to offer loans in certain areas) on housing in cities and towns were enacted. These reinforced the segregation of Mexican colonias like San José’s old Pueblo neighborhood, located next to the less desirable industrial area filled with canneries, packing houses and railroads.

As more seasonal Mexican immigrant workers arrived in the Valley, civic leaders worried that a In 1900, Mexican and ethnically white Portuguese, Spanish and Italians resided in the Downtown Colonia. When the number of Italians moving to the old Pueblo, between the 1880s to the 1920s, expanded beyond the housing capacity, they moved into the northern, western and southern adjacent neighborhood. The southern neighborhood became known as “Goosetown”. Throughout California, Mexican colonias were pejoratively called "Mexicantowns" or "Jimtowns" (thus racially equating Mexicans to southern African Americans, who were subjected to Jim Crow laws). Historian Suzanne Guerra notes, in the 1920s, the old Pueblo, referred to by Anglo Americans as “Mexicantown”, was hemmed in by urban development and adjacent orchards resulting in fewer places to live in San José. Historian Gregorio Mora-Torres observes that by WWII, the Italian residents of the Downtown Colonia and “Goosetown” moved to other neighborhoods throughout the city. WWII also enabled ethnic Mexicans to move up to higher paying, more stable jobs in the unionized canneries, so they bought the vacated Italian homes in the Downtown Colonia.

During the 1940s, the Downtown Colonia expanded north to St. Augustine, south to San Carlos Street, and west beyond the Guadalupe River. By the late 1950s, it had reached all the way to Home/Virginia Streets. Mexicans also lived in the community north of Santa Clara Street and between Second Street and the Coyote River. This spurred the development of Mexican owned businesses downtown to serve Spanish speaking residents in the region.

Title: San José Sanborn Map 1915 annotated

Date: 1915

Collection: California Room

Owning Institution: San José Public Library

Eastside San José

The area known as the Eastside San José was first settled by Puerto Ricans, who left low-paying Hawaiian canefield jobs during WWI for higher paid agricultural work in Santa Clara County. Prior to WWII, concerned that Mexicans might move into their neighborhoods, Santa Clara County civic leaders imposed racial/ethnic restrictive covenants and endorsed redlining policies towards Mexicans. This would concentrate the Mexican populations into the Downtown Colonia or the unincorporated Eastside. Mexican migrants and exiles from the Almaden Mine joined the Eastside Puerto Rican settlement in the early 1920s. These mineworkers wanted to be near other Spanish speakers as well as cannery and farm jobs.

In 1931 the Mayfair Packing Company, for which the Mayfair District is named, was built on the Eastside and became one of eleven canneries and packing plants in San José. During WWII, ethnic whites left for higher paying munitions industry work and Mexican workers filled cannery jobs and settled there in large numbers. In 1955 the Mayfair District, nicknamed "Sal Sí Puedes" (Get Out If You Can-a name taken from an original Mexican landgrant), was home to 4,500 residents, of whom 3,000 were of Mexican descent.

The segregated Eastside provided empty lots for group camping, mobile rail housing, or long-term housing in apartments, boarding houses, and rental units. Families would often pool their money to purchase an unimproved lot where they could build their own homes. In this way, worker neighborhoods were created with a variety of owner-built housing. For decades the segregated Eastside area remained unimproved with no paved streets or street lights.

Title: The Weekly Mayfair

Collection: History San Jose Online Catalog

Owning Institution: History San José Research Library

Source: Calisphere

Permalink: https://calisphere.org/item/0653be5aee3055fe70dd9fe65b695326/

Community Segregation Policies

Similar to Southern California, ethnic Mexicans were subjected to social, residential and educational segregation throughout Santa Clara County. According to a 1950 SJSU student study and a 1978 study done by the Garden City Women’s Club, ethnic Mexicans, African Americans and Asians experienced de facto segregation in policies regarding public pools, bowling alleys, and ballrooms and dancehalls.

Santa Clara County followed California’s segregationist housing policies, which also aligned with school segregation patterns. According to California law, segregated schools were built if a community had more than ten students of Native American, Chinese, Japanese or Mongolian ancestry and if these minority students’ parents petitioned a district to build one. If the community had less than ten non-white students, these students would only be allowed to attend the community school if white parents approved. If not, then these non-white students could not attend school. Students of Mexican ancestry were not included in California’s school segregation laws until their numbers increased by 1910 due to the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) pushing people out of México and the need for agricultural labor pulled Mexicans to the U.S.

Since many ethnic Mexican families migrated to new jobs every two to three months following the crops, their children’s school attendance could be sporadic. At that time, schools were divided between elementary (K-8) and high school (9-12). Since few employment opportunities existed outside of agriculture before WWII Mexican children were encouraged to work in order to supplement the family income or drop out of school after the 8th grade. After WWII, educational opportunities changed for ethnic Mexicans. Young people began attending high school and college, and skilled, higher paying jobs opened up to them. In post-war California, attitudes toward ethnic Mexicans slowly changed. Ethnic Mexican soldiers had become “brothers in arms” during the war as they fought in Anglo units, not segregated as African American soldiers had been. (See Civil Rights section for court cases and the ending of California school segregation.)

Title: Mayfair School Class Portrait with Christmas Tree, c. 1940

Date: 1935-1950

Collection: History San José Online Catalog

Owning Institution: History San José Research Library

Source: Calisphere

Permalink: https://calisphere.org/item/ac5699114d7befb729677d8c6cae3988/

Mythologizing the Past While Discriminating in the Present

Ironically, in the 1920s and 1930s, at a time when Mexicans were being pushed to the economic and geographic periphery of San José, Anglo city boosters promoted a parade, Fiesta de las Rosas, celebrating the region’s so-called Spanish (European) or “civilized” history. The event started as The Rose Carnival in 1896 and became the Fiesta de las Rosas in 1926 and lasted until 1933.

In this instance, as historian Stephen Pitti notes, Anglo citizens connected their shared European white heritage with an imaginary Spanish-European California, an explicitly non-Mexican past. A few of the region’s remaining Californios were considered worthy of celebration, such as Santa Clara’s Encarnación Pinedo. Historian/journalist Carey McWilliams observed that the Anglo population considered these particular Californios to be the living embodiment of the “Spanish fantasy heritage.”

During the 1910s and 1920s, fiesta parades took place throughout California and were wildly popular, particularly in Los Angeles and Santa Barbara; some continue on today. Celebrations and theatrical performances using the themes of California’s mythical past were held throughout California in plays like “The Mission,'' by John S. McGroarty.

Santa Clara County hosted its first performance of “The Mission'' in 1915 at Santa Clara University. As PItti states, concerns over racial miscegenation and inter-racial romance were followed by two Fiesta plays that celebrated European White (Spanish or English) conquest over Mestizos and Indians, “La Rosa del Rancho, a Love Story of Early San José” (1927) and “The Madonna of Monterey” (1930). Anglos and ethnic whites played all the Spanish roles. For the audience, these celebrations affirmed the dominance of white European culture over the darker skinned Mexican “peons,” who were securely marginalized.

TItle: 1927 Souvenir of the Santa Clara County Second Annual Fiesta de las Rosas

Date: 1927-05

Collection: Fiesta de las Rosas Collection

Owning Institution: San José Public Library, California Room

Source: Calisphere

Permalink: https://calisphere.org/item/efc8cd7b4b1b14869244f43bc824d234/

Mexican Mutualistas, Home Clubs and La Comisión Honorifica in Santa Clara County

In Santa Clara County, immigrants formed associations with others from their original home in México or other regions of the Southwest. In San José, historian Stephen Pitti describes the rise of “town clubs” as the fraternal twin of the Mexican American mutualistas, or mutual aid societies. One important difference was that both men and women joined the town clubs while mutualistas were for men only. In the late 1920s, town clubs and mutualistas both helped with life insurance and funeral expenses for those without funds, fostering “a sense of local identity” while maintaining cultural and nationalist connections to México.

Town clubs linked transplanted Mexican residents from similar hometowns that were now living in Santa Clara County. These community organizations assisted families, developed community and promoted cultural events. They held social activities in local parks and residences to raise money to aid members and celebrate cultural ties, such as Fiestas Patrias. Most importantly, they advised newcomers in their native language on local laws, customs, and practices to help them integrate into American society. While Americanization programs were designed to replace immigrants’ native tongue and cultural traditions, town clubs and mutualistas aided immigrants in their transition to the new country.

Mutualistas and town clubs strengthened links to the Mexican consulate and to México as well. Using these connections, the consulate encouraged repatriation to México for San José immigrants struggling in the U.S. during the Great Depression. The Mexican consulate in San Francisco worked with the mutualistas to promote Mexican national celebrations of the Fiestas Patrias and to aid Mexican citizens.

During the Great Depression, the town clubs grew because it was impossible to afford annual visits to México as had been common in the 1920s. The California deportation campaign against ethnic Mexicans between 1929-1934 reinforced Northern California Mexicans’ reliance on their town clubs.

Prior to WWII and after, non-citizens were usually ineligible for social services. Mutualistas played an important role in redressing these inequities, advocating for their members with police and immigration authorities and granting small loans, as well as sponsoring local sporting events and cultural celebrations. The Mexican Consulate established the Comisión Honorifica Mexicana, an organization to promote cultural connections and aid Mexican citizens in the United States. The Comisión admitted all men of Mexican descent, regardless of citizenship.

Title: Court of Fiestas Patrias, Trinidad de la Grande on the right

Date: 1940s

Collection: Before Silicon Valley Project Archive, Trinidad de La Grande Martinez Collection

Owning Institution: SJSU Special Collections

The 1930s Deportation/Repatriation Campaign in San José

In Santa Clara County, Mexicans did not endure the same threats from the Klu Klux Klan that their compatriots in Southern California experienced in the 1920s. However, with the 1924 Immigration Act, pressure was put on the U.S. federal government to establish the first Mexican border patrol.

In Southern California, the Mexican Deportation Campaigns from 1929-1934 further limited immigration. Santa Clara County, however, did not conduct extensive deportation campaigns, although Anglo trade unions tried to do so during the Great Depression. Instead, the Mexican consulate promoted the idea of repatriation to México to help those Mexican nationals who were suffering from the economic fallout from the Depression. As non-citizens, this population was ineligible for state or federal aid. During the 1930s, according to History Unfolded, 400,000-1 million of the nearly two million Mexicans living in the U.S., including American citizens, were either deported or repatriated to México. In San José, one third of the 4,000 Mexican residents chose to return to México in the Mexican government sponsored repatriation campaign.

Title: Article on Repatriation

Date: 04 March 1933, Sat. p. 4

Collection: Monrovia News-Post, Monrovia, CA

Source: https://www.newspapers.com/clip/69883035/monrovia-news-post/

Mexican Businesses in Downtown San José, WWII to 1960

Historically, American settlement was concentrated east of the old Pueblo, with new businesses on 1st, 2nd and 3rd Streets. The ethnic Mexican residents of Santa Clara County considered Market Street the line between the American area and the Mexican Downtown Colonia. Restrictive housing policies had created segregated neighborhoods, and it was commonly understood that public accommodations were racially restricted until the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Stores, restaurants, bars, and shops that served Mexican customers were located on Market Street or the portions of 1st, 2nd, or 3rd Streets south of Santa Clara Street. On weekends, Mexican workers from across the County congregated to do their weekly shopping, see a movie, or get a haircut. By 1960, Mexican Americans and Mexican nationals comprised one-fourth of Santa Clara County’s population and were a major factor in the regional economy. Urban redevelopment and freeway construction would displace a large number of residents of the Downtown Colonia, contributing to the closure of many Mexican businesses in the area.

Title: Pantoja Family in Downtown San José

Date: 1955

Collection: Before Silicon Valley Project Archive, José Pantoja Family Collection

Owning Institution: SJSU Special Collections

Mexican Entertainment in Downtown San José, WWII-1960

Downtown San José was the regional social hub for Mexican residents. On weekends, locals were joined by farm workers from nearby rural regions of the San Joaquin Valley to eat at a Mexican restaurant, watch a Spanish-language movie, meet friends for a drink, or go dancing.

On Market Street a strip of restaurants and stores catered to a Mexican clientele. After WWII, the Liberty Theater, the Victory, the Lyric, and the José offered first-run movies from México and staged personal appearances from singers and performers. Local ballrooms (see ballroom section) also enlivened the downtown social scene. The proximity of nightclubs, many Mexican restaurants and shops that encouraged their patronage, was a major draw to those who had only limited services in their small communities or the work camps scattered throughout the region.

After WWII El Eccentrico, the local Spanish-language entertainment magazine, established in 1948 (running until 1980), carried ads for shops, grocers, restaurants, and real estate and insurance agents catering to a Mexican clientele. Alongside the ads were announcements of clubs, concerts, and community events.

Title: “El Eccentríco” Cover

Date: Dec. 1950, Vol. 1, No. 10

Collection: “El Eccentrico” Collection

Owning Institution: California Room, San Jose Public Library

Source: Calisphere

The Influence of Mexican Music on San José, WWII to 1960

In 1942, the U.S. government instituted the Emergency Farm Labor Program, known as The Bracero Program, bringing in a new group of immigrants from the border regions along with a new style of music called Norteño or Tejano. The musical traditions of the Tejanos of South Texas and Norteños of Northern Mexico have been influenced not only by the mother country, México, but also by their Anglo American, African American, and immigrant neighbors like the Czechs, Bohemians, and Moravians as well as the Germans and Italians. From these influences came the polkas and accordion music that are so closely associated with this style.

Many of these Mexican immigrants were from rural areas, and more familiar with the Mexican orquesta tipica, or string band, and regional music from their homelands, such as the conjunto. The conjunto mixed the folksy storytelling corrido, the dance form huapangos, and the traditional ranchera with European instruments such as the accordion. In the borderlands of the American Southwest, the orquesta Tejana was patterned after the big bands of this period and appealed to an acculturated Mexican American audience. A fusion of these styles with mariachi and rock-n-roll in the late 1950s would result in a new style referred to as Tejano or Tex-Mex.

Mexican corridos, a popular music genre of the late 1920s to the mid 1940s, provided a way for ethnic Mexicans to document their immigration, migration, work and day-to-day living experiences. Frontera music curator Juan Antonio Cuellar notes that corridos were a form of oral history documentation adapted to music. News headlines became corridos stories. Cuellar describes corridos as “the newspapers of the Mexican working class”.

During the 1920s, Latin American music and performers became popular among elites of all continents, who often preferred simplified romantic ballads and Latinized American pop music. Both this “society rumba” and Afro-Cuban influenced Latin American music such as mambos, were popular with local Latino audiences for the next several decades. Out of the big band era arising in the mid 1930s through the 1940s, Mexican musicians added a Mexican twist and created Pachuco Boogie.

The largest events in San José were often held at the Municipal Auditorium, with performers such as Tito Puente, Desi Arnaz, and Lalo Guerrero playing for dances. Other ballrooms included The Balconades and The Palomar/Starlight ballrooms. During the war years, big bands–such as Benny Goodman, Glen Miller, Xavier Cugat, Jimmy Dorsey, and Artie Shaw–all featured Latin songs. In the early 1950s, American bands playing the Latin rumba, including nightclub performers such as Xavier Cugat, Desi Arnaz, and Carmen Miranda, were often featured in movies and television.

Title: Pérez Prado Band

Date: circa 1950

Collection: Before Silicon Valley Project Archive, Clay Shanrock Family Collection

Owning Institution: SJSU Special Collections

San José Sabor: Local Mexican Musicians, Singers, Bands and Radio Stations in San José, WWII to 1960

San José gave rise to several nationally recognized musicians and singers, such as the Montoya Sisters from the Eastside. From the 1940s through the 1960s, Agustin De La Grande was an important performer who, through his Academia de Musica, mentored many aspiring local musicians and young people in his marching band and orchestra. Agustin taught his daughter Trinidad De La Grande Martínez as well. She learned to play several instruments and filled in positions in her father’s band when needed. Some of De La Grande’s students went on to form their own groups, like the Bernie Fuentes Band, the house band at the Palomar. Low pay for performances forced many musicians to work during the day, many in the canneries, and perform in the evenings after work. This was the experience of musician Coronado Barrientes, drummer Rudy Coronado, and singer Francis Pacheco Wells.

By the 1950s, young Mexican Americans, like their peers, were attracted to the new musical styles of rhythm and blues and rock-n-roll. During this time, radio was becoming the prime source of Spanish-language entertainment and information for the expanding Mexican colonias. Many ethnic Mexicans could not afford to buy records or attend concerts, but they loved listening to music in public spaces that had jukeboxes or on the radio. Several local radio stations developed Spanish programs, some of which were broadcast by Jesus Reyes Valenzuela, born in Shafter, Texas, and the first Spanish language broadcaster to operate in Santa Clara County. In the late 1940, his "Hora Artistica" was aired on KSJO Monday through Saturday. Mornings and afternoons featured the beloved singers of Mexican rancheros--Pedro Infante, Jorge Negrete, Luis Pérez Meza, Luis Aguilar, and Lola Beltran. Radio Station KAZA in Gilroy started in the 1950s or 1960s. It was Portuguese owned and had 80% Spanish language programming, 7% Portuguese language programming and the remainder was English programming. In the 1960s, radio stations began to feature live remote broadcasts from community events featuring local singers and musicians.

Title: Exhibit De La Grande Colln_Agustin De La Grande Directing_other performers.tif

Collection: Before Silicon Valley Project Archive, De La Grande Collection

Owning Institution: SJSU Special Collections

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

- Remote video URL

Mexican Dancehalls, Lounges and Ballrooms

Public dance halls in the U.S. first appeared in urban areas around 1845, often as dance halls associated with the working classes, selling liquor or operating as saloons. In polite society, public dances were charity events, club or lodge dances, and held at dance palaces or pavilions associated with amusement parks. Providing a new social setting where people could make new acquaintances and socialize with those of diverse backgrounds, while observing the latest trends and fashions, ballroom dancing altered social patterns between the sexes, different social classes, and different racial and ethnic groups at the turn of the 20th century.

With the growth of popular music and dancing came new neighborhood dance halls or private clubs. Public dance halls and pavilions, often offering dancing lessons, did not appear in local city directories until 1927. From 1927 to 1945, four main ballrooms were located in downtown San José: The Balconades on Santa Clara Street, The Rainbow Ballroom on San Antonio Street, The Majestic on Third Street, and The Palomar Gardens on Notre Dame Street. These offered music by varied racial/ethnic bands in front of an integrated audience, although a majority came from the same racial/ethnic group as the band playing. In 1946, two other local venues were added: The Italia Hall, operated by Prospero G. López, and The Townsend Hall, owned by Frank and Angelo Boitano. These informal settings often catered to the non-Anglo working class and ethnic communities who could not afford, and often were not welcome, in the major ballrooms. In the late 1950s, John Zamora, a local Mexican businessman who had grown up as a farmworker and then went on to college, opened several restaurants with lounges where his musician brother Bobby Zamora and his band performed.

Music producers, such as Frank Davila, understood that the availability of both radios and record players to a wider audience helped to popularize new artists and sell records. While lounges and nightclubs offered an audience of 300-500 each night, large ballrooms might attract 3000-5000 potential record buyers. These large venues were ideal for aspiring performers and big-name attractions with new albums. During the 1930s, large public dances and concerts were held at The San José Municipal Auditorium, offering traditional Mexican and “Spanish-American” music. According to public historian Suzanne Guerra, who did an historical context on the last surviving ballroom from the Big Band Era, The Palomar, constructed in 1946, was the only venue where an integrated audience could attend social dances and musical concerts in an elegant setting.

San José provided numerous performing venues. Although not as large a market as Los Angeles, the proximity to the Bay Area and the many small venues in Santa Clara County enabled musicians to supplement jobs in the canneries with weekend performances at dance halls and clubs. This was the experience of Francis Pacheco Wells, vocalist for Dan's Combo, performing on the weekends at Maria'a Cocktail Lounge (728 N. 13th St. San José). Family celebrations and community fundraising events were often held at ballrooms and public halls. Musical parties like the multigenerational tardeada reinforced family and community ties, with both traditional musical styles and contemporary music, food and entertainment for largely Spanish-speaking audiences. In this way, the mix of musical styles in San José was continually renewed with each wave of immigrants and their distinct musical traditions.

Title: EL Eccentríco

Date: August 1949

Collection: EL Eccentríco Collection

Owning Institution: California Room, San José Public Library

Source: Calisphere

San Jose’s Zoot Suit Riots

The Zoot Suit Riots in 1943 were a series of violent clashes in Los Angeles between U.S. servicemen, off-duty police officers, and civilians who confronted young Latinos and other minorities. The riots took their name from the baggy zoot suits that accentuated their movements worn by many young men in the 1930s in dance halls in the East. The zoot suit became a popular trend among young men in African American, Mexican American, and other minority communities in California. Anglo Americans knew very little about the Mexican American community, who were generally portrayed by local police and newspapers as problematic lawbreakers, drunks, or criminals. Young Mexican Americans were portrayed as pachucos (juvenile delinquents) or gang members who posed a danger to society.

Conflicts between police and Mexican youths spread from L.A. to the Bay Area during the summer of 1943. In San José police carried out a similar harassment of Mexicans in the name of “keeping the peace.” In one instance, “intent on starting their own ‘zoot suit’ war,” a group of sailors hunted down Mexican youths as they spilled out of the downtown dance halls and ballrooms on Market Street in the late hours of the night. Local Judge William James stated, that "we certainly don’t want to see anything happen here like it is in Los Angeles,” handing down probation if the arrestee would join the military.

Large groups of assembled Mexican young men were often considered suspect. One night, two San José police officers tried to arrest two Mexicans having a fist fight in St. James Park. The two escaped but were caught in front of a dance hall where a group of Mexican cannery workers and zoot suiters were just leaving. The group attacked others, who followed the officers and the youths back to the police station. When the youths fell and appeared injured, a large group of military and local police arrived to disperse the crowd.

At a local Santa Cruz beach, Marines drove visiting Mexicans away. Five Mexican young men were held in the San José Jail “because of their large size.” In 1944, 25 zoot suitors were arrested for “frequenting streets and public places in the late night,” and three of what the San José police considered “bad boys” were deported to México. That same year, Gilroy police arrested thirty Mexican youth “for violating curfew laws.” Toward the end of the War, another clash occurred between zoot suiters and sailors in St. James Park, the same location as the lynching of Tiburcio Vásquez in the late 1800s, ending with the arrest of the Mexican youths and release of the sailors.

Title: Kiki, Benny, Nando 1942

Date: 1942

Collection: Before Silicon Valley Project Archive, The Fernando Chávez Family Collection

Owning Source: SJSU Special Collections

Rock and Roll Riot of 1956

Few people have heard about what became known as the first Rock ‘n’ Roll Riot at The Palomar Ballroom on the night of July 7, 1956. Opened in 1947, the Palomar was the first integrated ballroom in San José, where big bands, vocalists, and jazz artists from across the country, México, Latin America, and the Caribbean performed in front of an integrated audience.

In 1956, Rock 'n' Roll was still new, and the big attraction that night was the now legendary Fats Domino, who arrived very late to a large crowd inside the ballroom and hundreds waiting outside. By the time the band started, some patrons were already drunk and unruly. During the intermission, beer bottles were thrown; then a brawl began as lights were smashed, chairs and tables destroyed, and many were injured. Nearly a dozen people were arrested.

Accounts of the brawl appeared in every major newspaper in the country, and the San Francisco Chronicle termed the affair a “Rock ‘n’ Roll Riot,” linking the music with the breakdown of public order. One week later the San José City Council considered a resolution to ban rock and roll at city-owned venues, eventually establishing a new ordinance requiring all drinks at concerts to be dispensed in paper cups. Just as the zoot suit had been used to criminalize youth of color in the 1940s, Rock ‘n’ Roll music was used to vilify another generation of ethnic young people.

Title: Palomar Ticket Line

Source: San Jose MercuryNews

Public Domain

Leisure Time with Social and Car Clubs

With non-agricultural jobs increasingly becoming available to ethnic Mexicans after WWII, more Mexican American youth began to attend high school and college. In the 1950s, a proliferation of social clubs, like Club Cuauhtémoc, provided a place for young ethnic Mexican urban professionals to gather. Some social clubs functioned similarly to town clubs, like The Del Rio Club, bringing together people from the same town or region. Some social clubs focused on public service, holding fundraisers for charitable causes or organizing around community issues such as voter registration and Latino candidates. Social clubs sponsored dances, such as the traditional formal Black and White Ball, organized outings such as picnics, or group activities, including bowling teams.

In the 1950s and later, lowriders in San José were mostly Latino, converting older cars for cruising, car shows, and design competition at events, adorning their cars with Mexican American imagery and vibrant colors. As small groups organized into regional clubs, lowriding became a multigenerational cultural activity, with the embellished car club jacket created to identify the local group. These “jacket clubs” were popular in San José, though local police banned them from 1986 to 2022 on the basis of preventing gang violence and related crime. The intersection of Story and King in the Eastside is now recognized as the meeting ground for generations of Lowriders and San José as a center of Lowrider culture.

As the Mexican American community became more established, new organizations were formed, such as the Mexican American Chamber of Commerce and the Mexican Masonic Lodge. The number of social clubs, ethnic organizations and fraternal associations increased among the post-WWII growing Mexican middle class and young professionals, who announced their activities regularly in the bilingual, regional entertainment magazine El Excentrico (FKA El Eccentríco). Church groups, clubs, and organizations were also involved in charitable activities and community projects.

Social clubs, sporting events, baseball and basketball clubs, and car clubs promoted ethnic consciousness, built solidarity, and sharpened organizing and leadership skills. They offered young Mexican Americans opportunities to compete on an equal basis outside the immigrant community. Such cultural activities generated networks, created bonds of solidarity, and provided a strong foundation for the Mexican civil rights movement to emerge within a flourishing community of musicians, artists, sportsmen, and club members.

Title: Bernie Fuentes Band, Club Cuauhtémoc Social Dance

Date: 1950s

Collection: Before Silicon Valley Project Archive, Brooks Family Collection

Owning Institution: SJSU Special Collections

Recreation at Parks, Churches, Beaches, Mountains and Beyond