Before Silicon Valley: Mexican Agricultural and Cannery Workers of Santa Clara County, 1920-1960 is a bilingual website research and education project highlighting the little-documented history of ethnic Mexican migration, work, cultural life, and civil rights activism in Santa Clara County from 1920 to 1960. This website project is under the fiscal sponsorship of San José Parks Foundation and the co-sponsorship of San José State University Library, La Raza Historical Society of Santa Clara Valley, and the Arhoolie Foundation.

Before Apple and Hewlett-Packard, the Santa Clara County was the world’s largest fruit and vegetable processing (canning) center from the 1920s-1960s. Industrial agriculture depended on an immigrant and migrant Mexican labor force picking in the orchards and fields prior to WWII. During and after WWII, Mexicans moved from migratory agricultural work to stable, higher paying cannery work, dominating that industry. This transition allowed for the development of permanent Mexican American colonias (communities), worker culture, and political organizations that contributed to the Mexican American civil rights movement.

Institutionalized discrimination against Mexicans existed from the time of the transfer of California from Mexico to the U.S. in 1848, up to the modern era. Within this multi-cultural community and workforce, both Mexicans and Mexican Americans suffered specific patterns of segregation and discrimination. While for the most part they were legally defined as white citizens, they were commonly viewed as interloping, non-white immigrants and became objects of discrimination, segregation, and violence, targeted by such groups as the Ku Klux Klan. In Santa Clara County, Mexican agricultural and cannery workers addressed the problems by generating a cultural identity that allowed it to become one of the most important, vibrant Mexican cultural communities in the Southwest during the 1940s and 1950s.

These settled Mexicans and Mexican Americans sought to rectify the social injustices they faced by forming early labor and political organizations, particularly after WWII. Mexicans in Santa Clara County contributed significantly to the growth of the Mexican American civil rights movement, including the rise of Mexican American social justice organizations such as the GI Forum and The Community Service Organization. Two of the most celebrated Mexican civil rights leaders, Ernesto Galarza and Cesar Chavez, began their careers in Santa Clara County in the 1940s and 1950s.

By the 1970s, Silicon Valley industries were bulldozing fruit farms and replacing them with tech factories, and long-time Mexican residents moved into the margins of urban work and community awareness of their important contributions to the Santa Clara County. Now forgotten, the history of Mexicans in Santa Clara County’s agricultural and cannery history is an important chapter in the story of California’s and America’s civil rights history-its labor struggles, ethnic resilience, and creative adaptation and cultural production as components in the fight for equality.

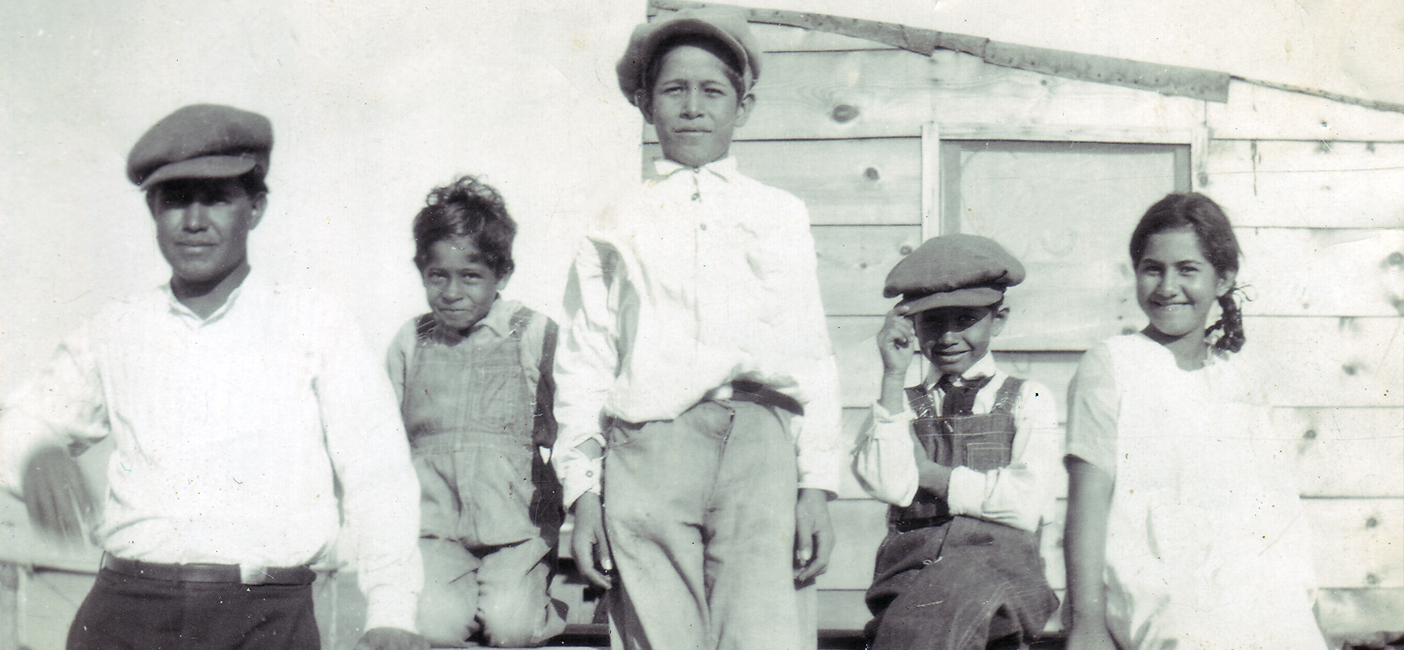

One of the unique aspects of this project has been the principal use of an extensive collection of oral history interviews with and personal photos of Mexican and Mexican American workers, artists, musicians, and community leaders. Interview clips have been incorporated into the mini-documentaries, and quotes from interviews are used in the Online Exhibit. The interviews were collected over a 50-year period. During the 1970s, Margo McBane collected the earliest interviews with agricultural worker Pearl Rios, 1930s CAWIU cannery organizers Dorothy Ray Healey and Elizabeth Nicholas, and CSO organizer Fred Ross Sr. We have also included information from a 1970s Mexican/Japanese/Spanish oral history project conducted by two Stanford University students, which now reside at Mountain View Public Library through the Mountain View Historical Association. Especially in dealing with previously undocumented history, community-based oral history techniques breathe new life into the writing of history. Mexican workers become active participants in the writing of their own story by sharing their lives, their photos and their network of community contacts. Through oral history and by establishing a basis of trust, historians can delve deeply into community memory.

We would like to thank our funders including County of Santa Clara’s Historic Grant Program, San José State University, NEH, Farrington Family Foundation, Santa Clara County Historic Grant Program, Silicon Valley Community Foundation, California Humanities, the City of San José’s Abierto Fund, and individual donors.